Claude Lévi-Strauss argued that the "savage" mind had the same structures as the "civilized" mind and that human characteristics are the same everywhere. These observations culminated in his famous book Tristes Tropiques that established his position as one of the central figures in the structuralist school of thought. Culture is the entire way of life of a society as well as all its products. Society is then composed of individuals who share a culture.

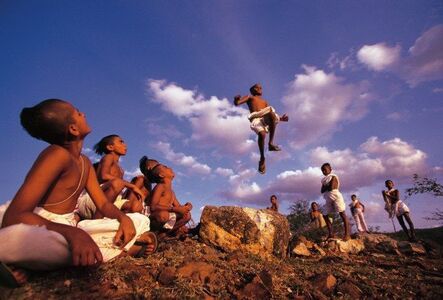

To be a member of society means sharing a culture. In this sense, a society is more than the sum of its members. Membership in a society necessarily involves sharing a way of life, engaging in similar patterns of thought and behaviour, such as bending low to touch the feet of elders as a sign of obeisance.

Human beings are not born with cultural patterns encoded into their DNA. No one is born Hindu, Bengali-speaking, and chanting the mantras. All such patterns of behavior have to be learned, and the more complex the society one lives in, the longer it takes to learn the necessary skills needed for competent social participation. Accordingly, most members of postindustrial societies spend long years in the educational system whereas member of the few remaining hunting and gathering societies have no need for formal education and rely rather on informal training. But however such learning takes place, informally with a relative or in a formal setting such as a school, it is vital for individuals to be able to become true members of society.

Nonmaterial culture comprises the ‘parampara’, the traditional hands down of society: specific shared ways of thinking shared by members of society such as language, beliefs systems, customs, myths, music, scientific knowledge or political ideas. And as mentioned above, culture also involves shared ways of behaving, such as participating in religious rituals or organized sports. These shared modes of thinking and behaving all constitute non-material or intangible culture.

Material culture also comprises all the ‘teachings’ of social life, that is, all the material and physical products of society: bows and arrow, buildings, computers, and all forms of technology. Technology consists in the material application of knowledge, scientific or other.

Human beings are the most creative species on the planet. It is the only species to have spread to all the continents, able to drive other species to extinction, and transform the environment to adjust to its needs, for better and for worse. Culture is the reason why the human species has been so successful and is therefore significant for several reasons.

Most animals are limited in their capacity to adapt by the slow process of biological evolution. In a sense, culture liberates humans from biological evolution in that it allows for faster change and adaptation. Cultural evolution and the cultural capacity to accumulate knowledge over generations have made biological evolution less significant a process. If we had to wait for biological evolution to develop the capacity to fly or travel great distances in a short period of time, we would still wait. Yet, technology, a product of culture, allows us to do just that. In this sense, cultural evolution is a faster, more successful extension of biological evolution.

At the same time, human beings are not completely free from some genetic and biological determinations: we have reflexes – unlearned automatic responses to physical stimuli such pulling one’s hand away from a flame, throwing one’s arms when thrown off balance or sneezing. We also have biological drives – unlearned biological responses to specific needs necessary for survival: food, drink, sleep, mating, and social companionship. These drives may be biological but we satisfy them through culturally acceptable means. Culture provides members of society with specific scripts that they are expected to follow in the satisfaction of their drives: table manners and dating rules are examples of such cultural scripts. Biology may explain the commonalities between human societies but culture accounts for the differences.

It is then extremely hard to draw a strict line between what is considered biological and what is considered cultural. We certainly have the biological capacity to laugh or cry but what makes us laugh or cry and under what circumstance such behaviour is appropriate is a cultural matter. It is also extremely hard to determine whether or not there is such a thing as human nature since many behaviours are the products of the interaction between biological needs and cultural experience. Appropriately enough, different cultures define human nature based on their own cultural scripts. For instance, in individualistic and competitive western societies, we tend to define human nature in exactly such terms. In other words, how we define human nature is a factor of the culture we happen to live in.

Similarly, culture forces to reconsider the question of human instinct. Instinct is often mistaken for reflex. However, instinct refers to genetically determined complex behaviour that all members of a species engage in at some point: spiders weave complex webs, birds engage in building nests of the same type. Even though some of them have never done it before, they instinctively know how to do it. If humans ever had instinct, it has been lost a long time ago and culture provides a substitute. However, it is because culture provides substitutes for biological evolution, human nature and instinct that it seems natural to us.

Another important characteristic of culture is that we tend to take our way of life as ‘natural”, that is, we take it for granted and as the “right” way of doing things. We therefore rarely question our cultural assumptions. In a sense, culture is invisible to us: it is just the way things are. We do not think we engage in specifically cultural practices when we buy items over the Internet using a credit card, work out at the gym or listen to a music CD. These practices just seem natural. This natural attitude has several consequences.

Because we tend to consider our cultural ways as “natural”, we often experience disorientation and discomfort when confronted with other cultures, a feeling known as culture shock. The greater the difference between the two cultures, the greater the shock.

Another consequence of seeing our own culture as natural is that we develop a tendency to judge other cultures by our own moral standards. We tend to consider ourselves more civilized: we worship the right divinity and our moral standards are better than those of other cultures. Such an attitude is called ethnocentrism. It is almost impossible to be objective about one’s culture and, in this sense, ethnocentrism can be a source of social solidarity and unity. However, ethnocentrism can also be a source of hostility, prejudice and conflict between groups. Also ethnocentrism can be a force of resistance to change. After all, if one considers one’s culture and tradition as better than others, why change?

Cultural relativism refers to the opposite attitude of trying to understand cultural practices in their own context, rather than judge them by the standards of other cultures. However, cultural relativism does not mean that anything goes, and that anything is acceptable. Cultural relativism is not moral relativism: Widow Remarriage, was considered a crime against humanity even if it made sense from the Pandit’ point of view. Therefore, cultural relativism is the attitude that any social scientist should adopt when examining other cultural practices without failing to notice if such practices are oppressive or violate human rights.

Because humans are not born with pre-determined solutions to most of life’s problems, they use culture as a toolbox that provides answers that are learned and shared. Culture provides material and non-material solutions to different problems: how to find food, deal with social relationships and the knowledge of human mortality, heal sickness and express emotions. In other words, culture provides ready-made but variable formulas on how to be a human being in a given society. And because the problems faced by human societies change over time, culture is dynamic as new solutions are needed.

Claude Lévi-Strauss considers culture a system of symbolic communication, to be investigated with methods that others have used more narrowly in the discussion of novels, political speeches, sports, and movies.

His reasoning makes best sense when contrasted against the background of an earlier generation's social theory. He wrote about this relationship for decades.A preference for "functionalist" explanations dominated the social sciences from the turn of the twentieth century through the 1950s, which is to say that anthropologists and sociologists tried to state the purpose of a social act or institution. The existence of a thing was explained, if it fulfilled a function. The only strong alternative to that kind of analysis was historical explanation, accounting for the existence of a social fact by stating how it came to be.

Claude Lévi-Strauss believed that modern life and all history was founded on the same categories and transformations that he had discovered in the Brazilian back country–The Raw and the Cooked, From Honey to Ashes, The Naked Man ,to borrow some titles from the Mythologiques. For instance he compares anthropology to musical serialism and defends his "philosophical" approach. He also pointed out that the modern view of primitive cultures was simplistic in denying them a history. The categories of myth did not persist among them because nothing had happened–it was easy to find the evidence of defeat, migration, exile, repeated displacements of all the kinds known to recorded history.