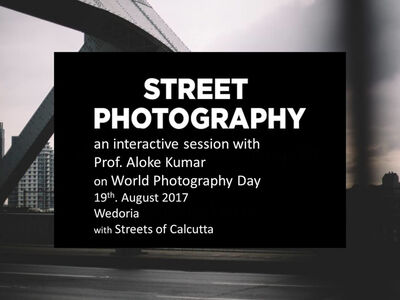

An interactive session with Prof. Aloke Kumar

On WORLD PHOTOGRAPHY DAY. 19th of August, 2017.

I am NOT a photographer. I am a Professor of Communication and visual communication or images forms a sub-text of my study. Like Mr. Bean who said: I sit in the corner and look at paintings. I look at photographs. What I like about photographs is that they capture a moment.

You don't make a photograph just with a camera. You bring to the act of photography all the pictures you have seen, the books you have read, the music you have heard, and the people you have loved.

In all of art history, it’s a challenge to find a term or a genre name that is as deceptively simple as street photography – this subgenre of photo making proved to be one of the most adaptive and malleable techniques of the last two centuries. It can still be a valid picture of this kind if it’s taken in a public environment in which one captures shots of by passers and regular surroundings, hunting the exact moment in time when the ordinary becomes extraordinary.

This particular genre of fine photography is probably best explained as an opportunistic moment in which a photographer captures a candid public scene in front of him. As was explained before, although there is the actual word street in the very title, this technique does not really tie itself to only pavements and alleys – in order for a street photo to be genuine, it has to feature an unposed situation within a public place, regardless of where that place may be. It can be the street, yes, but it can also be a bar, an inside of a train, a football match, cinema or a factory – it can be wherever you desire to take it and this is considered to be the most flexible aspect that gave street photography the reputation of rich variety and artistic freedom.

However, street photography seems to have one strict rule, which has been broken in a couple of instances even by the greatest names in the genre – it should be a true mirror of society, an unmanipulated scene with unaware subjects and unstaged settings. This is why street photography is often described as the most honest creative form ever invented as no amount of paintings, sculptures or films can rival the brutal honesty of just one good street photo. The magic of its chance interactions with everyday human activity within urban areas is undoubtedly the focal point of this genre and it falls second to nothing, not even the quality of the image or talent of the artist.

In the attempt to fully grasp the term of street photography, perhaps the wisest approach is to explain what it is not. Due to the unmanipulated approach, street photography has often been associated with its big brother, documentative image making, a strict and disciplined technique from which street photography had big problems of emancipating. The difference between the two is that, unlike documentaries and their archive-like methods, the general content of the scene or its precise location are irrelevant to the field of street photography.

In the years between the two World wars, several photographers had an immense impact on the subsequent maturing of street photography. As European artists were forced to take a step back while the war was going on around the Old Continent, the focal point of the genre moved to the United States. However, in the mid-1920s, photographers around Europe began working again – Hungarian photographer Andre Kertesz’s images of Paris, made after he adopted the 35mm camera device in the year of 1928 (Meudon (1928) and Carrefour Blois (1930)), display how the metropolitan life of the French capital used to look like with a strong note of surrealistic concepts.

The immediate post-war years inaugurated a particularly rich era in of street photography in the United States, as this was the only country whose domestic cities were not exposed to warfare. Several key street photographers like Lisette Model, Eisenstaedt, Helen Levitt, Louis Faurer, William Klein, Saul Leiter and Robert Frank authored some of their most renowned photos between the years of 1940 and 1960. Every single one of them brought something new to the table and helped develop the genre that was experiencing a significant rise in popularity in those years.

Henri Cartier-Bresson was a French humanist photographer considered a master of candid photography, and an early user of 35 mm film. He pioneered the genre of street photography, and conceived of photography as capturing a decisive moment. His work has influenced many photographers. In early 1947, Cartier-Bresson, with Robert Capa, David Seymour, William Vandivert and George Rodger founded Magnum Photos. Capa's brainchild, Magnum was a cooperative picture agency owned by its members. The team split photo assignments among the members Cartier Bresson is considered as the father of street photography.

The Second World War brought the American Gis to Calcutta. They were free, roamed the street amused by the variants and took photographs. The most important was Clyde Waddell. He was an American military photographer known for his photographs of Calcutta in 1945 Waddell was chief photographer for the Houston Press before entering the US Army and coming to the India-Burma Theatre in November 1943, where he was attached to the Public Relations Staff of Southeast Asia Command 'with the express purpose of acting as personal press photographer for Supreme Commander Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. On his return he published an album.

Raghubir Singh (1942–1999) was an Indian photographer, most known for his landscapes and documentary-style photographs of the people of India. It is Singh who introduced Colour to Street Photography. Raghubir belongs to a tradition of small-format street photography, pioneered by photographers like Henri Cartier-Bresson, whom he met in 1966 and observed for a week while the latter was working in Jaipur and who, with Robert Frank, was to have a lasting impact of his work; however, unlike them, he chose to work in colour, as for him this represented the intrinsic value of Indian aesthetics. In time Singh was acknowledged as one of the finest photographers of his generation and a leading pioneer of colour photography.

It is Mrinal Sen who introduced Street Photography to Indian Cinema by his cinéma-vérité style. A style of film-making characterized by realistic, typically documentary films which avoid artificiality and artistic effect and are generally made with simple equipment. His film, Bhuvan Shome finally launched him as a major filmmaker, both nationally and internationally. Bhuvan Shome also initiated the "New Cinema" film movement in India. It is in this film that he introduced Street Photography. Mrinal Sen’s movies from Punascha to Mahaprithivi, has shown Kolkata as a character, and as an inspiration. He has beautifully woven the people, value system, class difference and the streets of the city into his movies and coming of age from Calcutta to Kolkata. Above all it.