Apeejay Bangla Sahitya Utsob

20th, July 2019 at Oxford Bookstore

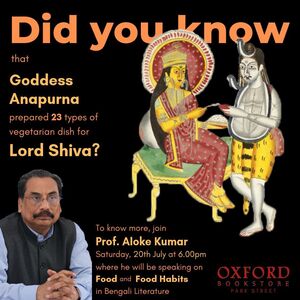

Prof. Aloke Kumar presents the History of Food and Eating Habits in Bengali Literature from Shiv to Vidyasagar. From Puran to Debganar Martya.

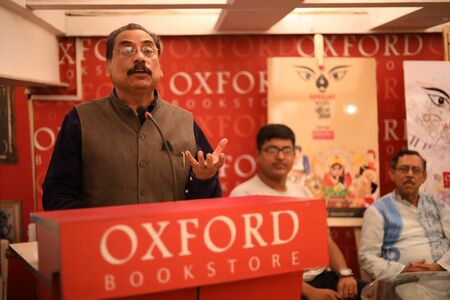

Bengali Literature has covered the most diverse and dynamic themes that could have been conceived. One such prominent theme in the City of Joy, is Food. Kolkata is much more than Paturis, Rosogollas, Ilish Maach and Mishti Doi. These and much more will be in a unique panel discussion titled- Bangla Sahitye Khaoa Daoa- presented by Apeejay Bangla Sahitya Utsob. The panellists included Prof, Aloke Kumar, Academician and Social Commentator; Haripada Bhowmik, Food Historian, Researcher and Author; Kaushik Majumdar, Author & Agro-Scientist and Indrajit Lahiri, published Author and Food Blogger.

No discussion on food in Bengali can take place without first mentioning the Goddess of Food, Annapurna. Annapurna meaning, possessed of food is the goddess of food in Hinduism. Annada Mangal is a Bengali narrative poem in three parts by Bharatchandra Ray, written in 1752-53. It eulogizes Hindu goddess Annapurna worshipped in Bengal. It has many details of food cooked by Ma Anapurna.

In the sacred texts of Bengal, in a verse of Halayudha’s Brahman- Sarvasva, (10th Century) the culinary culture of pre-colonial Bengal lays down the many features distinguishing it from other parts of the country.

Jimutavahana, a 12th-century poet, in his Kalaviveka writes that the Hilsa fish and its oil (in which the fish is fried) were popular in Bengal.

Shriharsha’s Naishadhacharita, a Sanskrit Mahakavya composed in 12th century, provides the picture of the Bengali eating culture. Nala and Damayanti are the protagonists. At their wedding feast, different dishes are served: such as cooked vegetables, fish, mutton, deer meat, different varieties of pitha (a kind of sweet dish), flavoured drinks and tambul or pan.

A verse from the Prakrita Paingala Sutra, composed approximately in the 13th century by Lakhinath Bhatta, depicts the interesting eating culture of that time. The verse says:

oggarabhatta rambhaapatta, gaika ghitta dugdhasajutta |I

mainimaccha ṇalichagaccha, dijjai kanta kha punabanta ||

[‘Fortunate is the man whose wife serves him on a banana leaf some hot rice with ghee, mourala fish, According to Narayan Deb’s Manasamangal, (15th century) at the wedding of Behula 12 types of fish and 5 varieties of meat were cooked, fried leaf of jute plant and some hot milk’]

Bengali culture started taking a recognizable form from the 15th century. The food habits of the Bengali people between the 15th and 17th centuries can be inferred from contemporary literature such as the Mangal Kavya and the Vaishnava texts. It is only in 15th-century texts, such as the Mangal Kavyas, that different kinds of dal and the process of cooking are mentioned.

According to Narayan Deb’s Manasamangal, (15th century) at the wedding of Behula 12 types of fish and 5 varieties of meat were cooked.

Abhaya Mangal by Mukundaram Chakrabarti in the 16th century, elucidates one of the most detailed descriptions of a Bengali vegetarian meal, the one that the god Shiva asks his wife Gouri to cook for him.

Mukundaram Chakravarti, in Chandimangal (16th century), mentioned multiple vegetarian and non-vegetarian dishes. Among those, Shukto (a bitter dish), prepared with Neem leaf, Seem, Indian pumpkin (Chalkumro) and Brinjal, were significant.

The narrative poem, Chandimangal 1752-53 (Bengali: চণ্ডীমঙ্গল) reveal many aspects of the social life. Though, these narratives were developed to describe the power of Chandi and establish her worship, it gives the food habits.

Mukundaram Chakravarti, in Chandimangal (16th century) provides detailed descriptions of Bengali dishes such as fulbori, fish chachchari, fried saral puti and prawn.

In a section of the Chandimangal, Mukundaram narrates a story where Phullara prepares some dishes for one of the main protagonists, Kalketu. They include boiled broken rice, lentil boiled in water with some spices and bottle gourd, burned native potato and Ol (an Indian vegetable), kachu and amda, and ambal (sour soup).

Other Puran and Kavyas such as Dharmamangal and Padmapuran also discussed the popular dishes in medieval Bengal. The text depicts other dishes in the same episode; including deer meat, burned mongoose and machar ghanto with amra.

We come to learn from Chaitanya Bhagavata, Madhya-Khaṇḍa (15th. Century) how Sri Chaitanya transformed Bengali food habits to a great extent. Sri Chaitanya and some of his associates appreciated good food but were strict vegetarians. Khichuri ‘, Hindi: खिचड़ी, Bengali: খিচুড়ি, was introduced as Prasad by Chaitnya. It is essentially a North Indian Dish. It is Chaitanya who introduced it as a Prasad and later went on to become one of the staple foods in Bengal.

Prem Abatar Sri Chaitanya by Tarakchandra Ray, 1876 that influenced by Chaitanya’s way, many of the respectable Bengalis did not consume non-vegetarian food, even the Shaktas partook of mutton and fish only on specific occasions. However, they sometimes ate deer and lamb meat.

Sarvananda, in Tika Sarvasva, shows the passion and love of east Bengalis for shutkimachh (dried fish). Among the spices, he said that marich (pepper), pippali, labanga (long or clove), jirak (jeera or cumin), ela, jafran (saffron), ada (adrak or ginger), karpur (camphor), jaifal (nutmeg), hing (asafoetida) were popular in Bengali cooking.

Ghulam Murshid in his book, হাজার বছরের বাঙালি সংস্কৃতি mentions that with the establishment of Islamic rule in Bengal the eating culture gradually took a different shape. Many new food items, such as watermelon, pomegranate, pulao, biriyani, kebab, kofta and kaliya were introduced by the Turks.

In the book Naba Babuvilas, published in 1830, Bhabani Charan Bandyopadhyay narrates the transition: In the 18th century, we find some important changes in food habits of Bengali. A large number of sweets, both fried and made of posset or cottage cheese (chhana), entered the cuisine.

In the book, Bengali Food by Babu Brajendranath Bandopadhyay, (1943) we find the food eating habits in East Bengal. In water-body–dominated East Bengal, fish eating was more prevalent. People there enjoyed diverse fish like kharsun, prawn, rui, chital, bain and shol. They were cooked with rich spices like green or red chilli paste and cumin. Turtle meat and eggs were also in demand.

Babu Brajendranath Bandopadhyay and Sajanikanta Das (1943) mentions that along with the Portuguese, another group of people who profoundly influenced Bengali culture were the Mughals. Nihal Chand in his Paus Parban talked of kalia, kebab, kofta, korma, polau, dum and bhuna as Bengali favourites. Meat cooked with onion, garlic and rich spices in Mughlai style became a part of the Bengali culture in the 18th century and continued till the early decades of the 19th century

Iswar Gupta, the poet recorded the fascination for mutton among contemporary Bengalis. Around the same time the demand for better quality of fish was growing amongst the urbanized Bengalis.

Bharatchandra lists bhetki, bacha, kalbos, pabda and ilish among the species of fish eaten by his contemporaries. Significantly, these names are not found in earlier, more rural poetic compositions.

Rajnarayan Basu’s (1826–1899) autobiography is an important text to understand the contradiction between the ‘western modern’ and the ‘alternative modern.’ When he became a Brahmo, he consumed biscuits and sherry as a protest against casteism, because at that time the industry of bread and biscuits was primarily run by lower castes or Muslims in Bengal.

In his autobiography Amar Jiban, Nabinchandra Sen (1847–1909) narrates a similar kind of story. According to him the primary force which made him a Brahmo was none other than bread, because in Brahmoism there was no restriction on the consumption of bread.

In 1860, Madhusudan Dutt (1824–1873), in his satirical play Ekei Ki Bale Sabhyata? illustrated the responses of the Bengali middle-class youth. In this work, a Vaishnava man follows some young people to learn about their activities. Among those young men was one named Kali, who suggested to his friends to feed the Vaishnava some fowl cutlet and mutton chop so that his life becomes meaningful.

In a different vein, Jogendrakumar Chattopadhyay (1867–1959), a renowned journalist, in his biographical sketch, narrates a story where the renowned social reformer Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar’s consumption of bread is justified as a diet prescribed by the doctor.

Debganer Martye Agaman by Durgacharan Ray is one such travel story where the writer depicts the reaction of the orthodox Hindus towards the reforms in the culinary culture in the colony. The primary plot of this novel is that of four male deities of the Hindu pantheon—Brahma, Narayana, Indra and Varuna—who came to earth in disguise of travellers visiting Calcutta goes to the Bengali home and reveals their food habits.