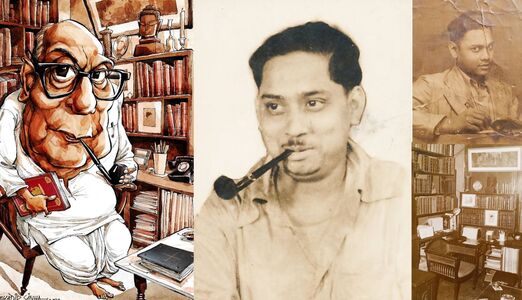

My father Nirmal Chandra Kumar, the antiquarian, has been compared to Satyajit Ray’s fictional character Shidhujyatha. R P Gupta in his writing has mentioned that Satyajit Ray modelled the character on my father who had an encyclopaedic knowledge on many subjects. History, Art, Archeology, Ornithology, Botany, Travel, Wildlife, Religion, Anthropology, Linguistic and many more. His vast knowledge came from his collection of books which he housed in a well-appointed library at his home in Taltala. Moreover, he was in the habit of collecting newspaper cutting which he kept in Journals. On the centenary of my father there has been several articles in newspaper where this aspect has been highlighted.

But no description fits him as well as that published in The Telegraph recently: Shidhujyatha’s revulsion to leave home. Shidhujyatha’s grouse lies elsewhere: that people wish to travel in the first place. For Shidhujyatha is the foremost, albeit fictional, advocate of the concept of manas bhraman, armchair travel. In Sonar Kella, the film, not the text, he tells Felu and Topshe that even though he could have done many things, he chose to do nothing; instead, he sits, motionless, with the proverbial windows to his soul open to let in light and air. This description fits my father so well and no one else whom I know.

In fact, for long, I did not know what my father did for a living. The whole day he would spend time in his library rummaging through antique books, maps and prints and then just sit smoking his pipe doing nothing. In the afternoon he would take a siesta, get up to paste newspaper cuttings in thich bound volumes which he called 'guard books'. In fact it is this habit of collecting newspaper cuttings that drew him to a Scrap Book on the Mutiny of 1857 which came up in an auction in Sotheby’s. He bid for the book and purchased it paying a handsome amount of £100, quite a high price in those days, for his friend Satyajit Ray who was then planning a film on the subject, Satranj ki Khilari. According to R.P.Gupta, a close friend, Ray did not forget this gesture and also the fact that Kumar had always helped him with books and innumerable information and facts, and paid him his biggest personal tribute. He based one of his characters in his story book series on Feluda, the detective, etched on Kumar. R.P comments that the character Shidhujyatha (Sidhuuncle) in the Feluda series, with an encyclopaedic knowledge immortalizes Kumar, who had a vast knowledge on many subjects. Incidentally, in his book, Stan Kal Patra, both Kumar and Sidhujata has been compared with another well-known Bibliophile, none other than Jorge Luis Borges.

As for me, in my school Don Bosco, in the primary section we would be asked by the teacher to go up to the front of the class and narrate ten lines on your father: I would lie and say that my father is a professor because that is the nearest image that was close to my father. I say nearest, as, can you imagine a stocky man, in a white collared shirt, half-sleeved, and a lungi smoking a pipe or a Davidus cigar sitting in his library surrounded by books the whole day doing nothing. But his friends have argued that Nirmal Chandra Kumar alias, Shidhujyatha was making a case for a cerebral life of immobility.

Sidhu Jetha's formal name is Siddheshwar Bose in the novel by Ray. He is an aged character who is a bibliophile, and has an extensive base of general knowledge, current and historical affairs. He is a close friend of Feluda's father, being former neighbours in their ancestral village in Bangladesh. Feluda's jyatha (that is, uncle) is said to have a 'photographic memory', and is a vast source of information which comes in handy when Feluda is in need of some. His vast knowledge comes from his collection of varied kinds of newspaper clippings which he has accumulated over the years.

My father, Shidhujyatha would have certainly found a kindred spirit in Immanuel Kant. The philosopher was never spotted too far away from his birthplace, Königsberg; he insisted that he had no time for travel since there was so much to learn , seated, about the world. This League of Anti-travellers should also include Joseph Hall, the pioneer of armchair travel writing, whose satirical and dystopian Mundus Alter et idem (Another World, and Yet the Same) can be read as a vicious spoof of The Travels of Sir John Mandeville. An eighteenth-century Frenchman can also be counted as the League’s honourable patron. Xavier de Maistre, Allen de Botton writes in an engaging article in Financial Times, most recently, had locked himself up in a room to study the ‘enchanting’ objects that lay closest to him. The result of his discoveries was wonderful: A Journey Around My Room — a travelogue that involved Xavier de Maistre ‘journeying’ from the bed to the sofa.

But the armchair traveller need not cover short distances only. Indeed, the armchair has helped the mind cross the veritable twenty thousand leagues, thereby serving as the allegorical pen that created canonical works in literature. Around the World in Eighty Days was written without Jules Verne having to circumambulate the planet. Rudyard Kipling could materialize “Mandalay” without stepping foot in that country. Then there is Chander Pahar, a rich, almost ethnographic, account, even though the distance between Africa and Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay village was infinite.

The 1650s, French philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal jotted down one of the most counterintuitive aphorisms of all time: ‘The sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he cannot stay quietly in his room.’ My father quoted this often with a smile through his pipe with eyes glittering.

But whatever be the guise of the traveller: crusader, king, merchant, explorer, slave-trader, empire-builder, those with roving eyes have ended up transforming, usually for the worse, the very world that they had sought to wander in. Now, the world has struck back in vengeance forcing humanity back to the armchair.

Did I see my father smiling?

~

Images : My father sitting in his arm chair in his library, more closer to the image of Shidhujyatha as depicted by Satyajit Ray.

My father, a stocky man, in a white collared shirt, half-sleeved, smoking a pipe.

My father at a much younger age when he tried his hand at writing, which in his words he failed quite miserably.

My father's library and the armchair. This was his favourite place with the phone at arms distance.