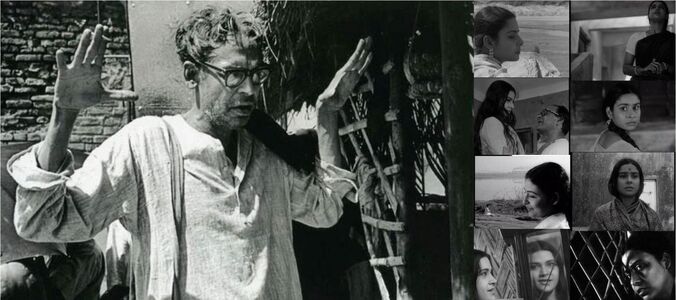

I was never a fan of Ritwick Ghatak. I found his films melodramatic and oozing sentiments. In my mind it lacked the artistic quality of a Satyajit Ray film or the cinematographic technique of Mrinal Sen. It delved on the subject of partition and as the Bengalis says ‘ghan ghanani’, loosely meaning repetitive. Bengalis have always been divided between the Ghotis and the Bangals and Ritwick fell in the category of the later: ‘ma kaisan’, mother said and ‘amago desh’, my homeland.

Much later during my course on film appreciation at St. Xavier’s College when Father Roberge pointed out the nuances of a Ghatak film that I started having a closer look and immediately thereafter went to Pune Film Institute to view a number of films among them Ghatak. It took a French Canadian Jesuit priest from the cloister of Prabhu Jesu Girja,not a Bangal by any imagination, to explain to us the films of Ghatak and that too the mileu that it captured.

I must confess that I could not really understand but felt the intensity of a Ghatak film. To my mind, like Kenji Mizoguchi of Japan and Rainer Fassbinder of West Germany, Ritwik Ghatak was an exponent of Melodrama, which refers not to soap opera dramatics but to a particular form of heightened expression in which film elements are pitched at a higher level than the realist norm. The result is a disruption of passive assimilation of screen drama and a motivation to critically engage with what is depicted. Ghatak is now considered by many critics as the preeminent Indian filmmaker.

The Bengali filmmaker, Ritwik Ghatak, was born in Dhaka in 1925, and lived the early part of his life in East Bengal, present-day Bangladesh. The Bengal Famine of 1943-44, World War II and finally, the Partition of 1947 compelled Ghatak to move to Calcutta.Twice during his lifetime Bengal was physically rent apart—in 1947 by the Partition engendered by the departing British colonizers and in 1971 by the Bangladeshi War of Independence. This continuously bothered him and became the ‘letmotif’ for all his films.

In his films, Ghatak constructs detailed visual and aural commentaries of Bengal in the socially and politically tumultuous period from the late 1940s to the early 1970s. In his work, Ghatak critically addresses and questions, from the personal to the national, the identity of post-Independence Bengal. The formation of East Pakistan in 1947 and Bangladesh in 1971 motivated Ghatak to seek through his films the cultural identity of Bengal in the midst of these new political divisions and physical boundaries.

Ghatak was an important commentator on Bengali culture. His films represent an influential and decidedly unique viewpoint of post-Independence Bengal. Unique, because in his films he pointedly explored the fallout of the 1947 Partition of India on Bengali society, and influential, because his films set a standard for newly, emerging “alternative” or “parallel” cinema directors,in contrast to those directors who opted for the hegemonic “Bollywood” style of Indian cinema.

The majority of Ghatak’s films are narratives that focus on the post-Independence Bengali family and community, with a sustained critique of the emerging petite-bourgeoisie in Bengal, specifically in the urban environment of Calcutta. In this context, Ghatak utilizes a melodramatic style and mode novel to Indian cinema. His melodrama combines popular and classical idioms of performance from Bengal and India that are merged with Stanislavskian acting and Brechtian theatrical techniques.

In his films, Ghatak consistently layers these three components to convey both utopian and dystopian visions of “homeland” in an independent Bengal. He employs Bengali folk music and frames Bengali landscapes to inform, both aurally and visually, his representations of Bengali women as symbolic images of the joy, sorrow and nostalgia that he associates with the birth of the Indian state.

In the 1950s, Ghatak became active in filmmaking. Ghatak’s films, Meghe Dhaka Tara (A Cloud-Covered Star, 1960), and Subarnarekha (The Golden Line, 1962; also the name of a river in what is now Bangladesh illustrates the critical relationship between women, landscape, and sound and music which is fundamental to his construction of a “resistant” narrative of the new Indian nation.

Ghatak viewed the division of his native Bengal as mishandled and ill-conceived. Government officials, he believed, gave barely a thought to the devastating impact that such a division would have on millions of people. Ghatak spent his entire artistic life wrestling with the consequences of Partition: particularly the insecurity and anxiety engendered by the homelessness of the refugees of Bengal.In his films, he tries to convey how Partition struck at the roots of Bengali culture. He seeks to express the nostalgia and yearning that many Bengalis’ have for their pre-Partition way of life.

In his films, Ghatak often situates his preoccupation with the union of East Pakistan and West Bengal within the heart of Bengali society: the family. And through the post-Independence Bengali “family,” Ghatak expresses the radical transformations that occurred within Bengali culture. Ghatak’s “families” are often not the traditional extended Bengali family, but “alternative,” “surrogate” families, like the theatrical troupe in Komal Gandhar or the wandering group of misfits in Jukti Takko Ar Gappo (Arguments and a Story, 1974), who are displaced, urban, lower middle class refugees searching for a home. By utilizing a melodramatic style comprised of Bengali, Indian, European and Russian elements, Ghatak visually and aurally articulates a new Bengali homeland.

Since I considered Ghatak’s film as melodrama let me point out my understanding. Melodrama as a mode, genre and style in Indian, specifically Bengali, literature, theater and cinema has always been there. Ghatak utilizes melodrama primarily as a style or mode rather than a coherently developed genre. He constructs his melodramatic style within the general Indian popular cinematic context of the 1940s and 1950s Hindi “social” films of directors like Guru Dutt and Raj Kapoor and the specific, regional context of 1950s.

In an attempt to refine the definition of “melodrama” in relation to “realism” in the context of Indian cinema it is necessary to understand the conceptual separation of melodrama from realism which occurred through the formation of bourgeois canons of high art in late nineteenth century Europe and America was echoed in the discourses on popular commercial cinema of late 1940s and 1950s India. This strand of criticism, associated with the formation of the art cinema in Bengal, could not comprehend the peculiarities of a form, melodrama, which had its own complex mechanisms of articulation. In the process, the critics contributed to an obfuscating hierarchization of culture with which we are still contending.

Ghatak as a filmmaker who unabashedly employs a melodrama modality that combined maudlin and Marxist elements, Ghatak often stands in a cinematic space in between the popular cinema of Bombay and the art cinema of Bengal. In Bengal, where a cinema had developed which was economically strong but culturally subservient to the novel, melodrama acquired an oppositional force.

Ghatak interweaves material from Indian mythology and Upanishadic, Marxist and Jungian philosophy into a melodramatic narrative form. He deliberately uses coincidence and repetition to educate an audience and to express ideas. In Ghatak’s 1963 article, “Film and I,” he writes that melodrama is a “much abused genre,” from which a “truly national cinema” will emerge when “truly serious and considerate artists bring the pressure of their entire intellect upon it “I am not afraid of melodrama. To use melodrama is one’s birthright, it is a form.” This statement itself is melodramatic as he could have stopped at “I am not afraid of melodrama.” But goes on to elaborate equating it to his birthright. Typical of Bangal sentiments.

Ghatak largely developed his melodramatic style of cinema when he was a playwright, actor and director during the 1940s and 1950s in IPTA. The variety of both indigenous and foreign theatrical styles that IPTA incorporated — such as the Bengali folk form, jatra, and Brecht’s “epic” form, greatly contributed to the theatrical shape of Ghatak’s melodramatic style. Ghatak’s films are frequently characterized as “epic”; he often inverts and recontextualizes Indian traditions and myths. He described Indians as an “epic-minded people” who liked to be told the same myths and legends again and again, and he viewed this “epic attitude” as a “living tradition.” In Meghe Dhaka Tara and Subarnarekha, Ghatak deconstructs traditional mythologies surrounding the Bengali woman, and his insertion of reconstructed representations into a modern context to critique his present historical moment.

The technical details of Ghatak’s melodramatic style include the following stylistic traits: frequent use of a wide angle lens, placement of the camera at very high, low and irregular angles, dramatic lighting composition, expressionistic acting style and experimentation with songs and sound effects. With this combination of cinematic devices, Ghatak creates a melodramatic post-Partition world in which he constructs his vision of “Woman” and “Homeland” in post-Independence Bengal.

In cinema, the family, the home, with women — mothers, wives, daughters and sisters as the key players — is the primary site of domestic melodrama. In Bengali culture, the home houses the heart of Bengali society: the family. And at the core of the Bengali family is ma, the mother. Within the homes of Ghatak’s post-Independence Bengal lies the site of both ananda (joy) and dukkho (sorrow), emotions intensely expressed by his female characters, frequently through song. These songs and music distill the essence or rasa of the joy and sorrow that Ghatak’s characters experience, and the music track enables these emotions’ full force and weight to be communicated to the audience. The ability of music and song to express powerful emotions beyond the visual dimension of a film, even beyond the film text itself, is particularly evident in Ghatak’s Meghe Dhaka Tara, and Subarnarekha.

In fact it is Ghatak who established the role of melodrama asserts the non-representational and reveals elements which cannot be conveyed through representational means alone, a fundamental shift that seems to guarantee the genre’s potentially ‘subversive’ effects.