It was end 1986. I was working in the ABP Group and to my surprise, received an invite from Father Gaston Roberge of St. Xavier’s College to a special screening of Maya Darpan. Released in 1972 the film did not do well in public halls, caused in part by Satyajit Ray’s scathing review of the film.

Kumar Shahani’s Maya Darpan is a seminal work in Indian Parallel Cinema not just because it canvasses critical social issues, a facet that, more or less, in hindsight, has become a characteristic of the movement, but also because it attempts to seek out a new aesthetic, which does not try to straddle mainstream cinema and art cinema, to do that. The very title, Maya Darpan, literally “Illusory Mirror”, aptly sums up both the film’s social, imprisonment by one’s own “image”, as defined by the class system and formal. Maya Darpan could well be a sobriquet for cinema itself, encompassing both its illusive and realistic properties at once.

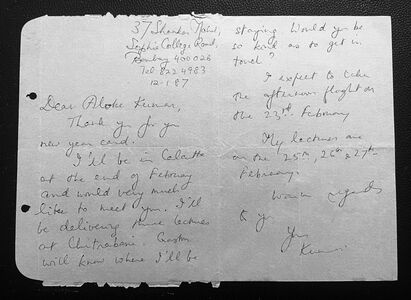

I was moved by the film and forwarded a card to Kumar Sahani, congratulating him and expressing my views on the film and my desire to meet him. I very promptly received a hand-written Inland Letter, that he would very much like to meet me and in fact is scheduled to come down to Calcutta on the invitation of Father Roberge to deliver a series of lectures. I did meet him and thus began a long relation which somehow got severed, I think due to my sudden hibernation from cinema. Today I came to know that he has passed away yesterday and that too in Kolkata. I did not know that he was in my city. What a loss! Maybe, I could have met him again and again.

The cinema of Kumar Shahani single-handedly established the cinematograph’s links with earlier pre-modern art forms whilst at the same time capturing the specificity of the film medium. As opposed to the ontological-realist conception of cinema, which finds its culmination in the bourgeois ideal of lyricism, Shahani’s cinema witnesses a return to the epic. The epic for Shahani simultaneously unites the lyrical with the dramatic and becomes the most accurate representation of history itself.

A student of Ritwik Ghatak at the Film and Television Institute of India, Shahani’s early work, such as his graduation film The Glass Pane (1965) and the short films Manmad Passenger (1967) and Object (1971), point towards a crisis in realist representation, as the characters neither consume nor act. Shahani’s cinematographic idiom is closer to an internal state or interiority. For Shahani, realism avoids the class conflict as well as the conflict of the known and the unknown, which find their resolution in myth, thus linking seeing with living.

Shahani’s debut feature, Maya Darpan (1972), links the epic tradition with an interiorised landscape through its non-psychological use of colour. Continuing the themes emphasised in Ghatak’s 1960 film Meghe Dhaka Tara (quoted on the soundtrack of the film), Shahani’s feature is about the conflict between oppressive feudal norms and a changing industrial landscape and their relationship with female sexuality through the textures of everyday life.

Taran, the protagonist, is the iconic-epic deity representing the Tantric figure of Kalikata. The film emphasizes the conflict between an arid landscape owned by a warrior caste handed down to a new generation of technological colonizers and the impact of capitalism that makes the landscape a mere natural resource. The film is fragmented by images and sounds that represent eruptions of anger representing working class agitations. Maya Darpan is structured according to the ajrakh technique of woodblock printing, which emphasises a multi-centered dynamic joined together by a rectilinear grid. It originates from Kutch in Gujarat.

The failure of Maya Darpan at the box office, caused in part by Satyajit Ray’s scathing review of the film, resulted in Shahani taking a 12-year hiatus where he took to writing as a form of expression. From 1976 he held a Homi Bhabha Fellowship to study the epic tradition of the Mahābhārata, Buddhist iconography, Indian classical music and the Bhakti movement. During this time, he took to teaching, known as a teacher and theorist of cinema, whose essays The Shock of Desire and Other Essays, comprising 51 essays.

Shahani’s next feature, Tarang, starring Smita Patil and Amol Palekar, transposed feudal patriarchy to the urban landscape of Mumbai in order to pose a simple question: did the Indian bourgeois contribute to the setting up of an independent state, during and after the freedom struggle or did they instead create the conditions for a militant Left? The film uses the epic of Urvashi and Pururavas to argue that myth is the most accurate depiction of history. The performative style of the film is based on Shahani’s research on Kuteyattam. Kuteyattam, Sanskrit theatre, which is practised in the province of Kerala, is one of India's oldest living theatrical traditions. Originating more than 2,000 years ago.

Shahani would continue his explorations between melodrama, being a student of Ritwick Ghatak, as a representative of the oppressed in a feudal patriarchy transformed by capitalist commodification, and its relationship to the star as represented by Shatrughan Sinha in his 1991 film Kasba.

Shahani increasingly focused on a classicisation of the everyday in his two intensely subjective films on music and dance respectively, Khayal Gatha (1989) and Bhavantarana (1991). Khayal Gatha juxtaposed historical and contemporary legends around the khayal form to emphasise shrutis as “approximations which are never absolutes”.

In Bhavantarana (1991), classical Indian dance is presented as a conflict between stylised labour and improvised movements that defy codification and classification. The documentary explores traditions of social initiation and their development into classical through dance maestro Kelucharan Mohapatra.

In his next feature film, released in 1997, Shahani turned to Tagore’s 1934 novel Char Adhyay, linking female sexuality with the nationalistic struggle. For this, he cast a trained Odissi dancer, Nandini Ghoshal, forcing the actress to forget her training to reach ‘the outside.’

The films of Kumar Shahani achieve a balance between process and realisation without ever making the concept or its practice into a fetish. Like Ghatak, he is a refugee, born in Sind, Pakistan, and his films are about this displacement that is represented through the camera, a mechanism to let in light and film a surface.

Shahani was born in Larkana, Sindh (now in Pakistan). After the partition of India in 1947, Shahani's family shifted to the city of Bombay (now Mumbai). He received a B. A. (Hons) from the University of Bombay in Political Science and History and studied screenplay writing and Advanced Direction at the Film and Television Institute of India, where he was a student of Ritwik Ghatak. He was awarded a French Government Scholarship for further studies in France, where he studied at the Institut des hautes études cinématographiques (IDHEC) and assisted Robert Bresson on Une Femme Douce.

Shahani had considered Robert Bresson and Roberto Rossellini as major influences on his work and those who he learned the most from. When comparing the two he stated, "There is austerity in Bresson. But there is a possibility in cinema to have both: austerity and ornamentation. In Bresson, there is mainly austerity even though he aspires to have spectacle. When I work along those lines, I want the ornamentation to stand out. The magic of that reality must appear and we ought to allow that to happen. The notion of ornamentation that we have in India, the alankar, of how we play with it, that is something I like to retain in my work. And this is not there either in Rossellini’s work or Bresson’s in the works of Catholic filmmakers. When they move towards austerity, they really move towards it: Bresson in the tradition of St Augustine and Rossellini more in the manner of notational narratives.”

For his film Tarang which dealt with labour issues, Shahani mentioned he consciously tried to avoid 'repeating' or 'imitating' one of his favourite films Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin. Shahani stated, "for Tarang for instance, I was shooting a strike sequence. It was an obvious point where one could have quoted Eisenstein. Most filmmakers in such a situation would do so, inadvertently and unconsciously. Even the most "bourgeois" filmmakers as it were, the most commercial ones, or their exact opposites, would all do that. That is why one should remember him, to remember what he did and not to repeat it. So I remembered him while I was shooting that sequence, constantly like a prayer. We can't help saying that Eisenstein did it such a way and let only him do like that. That is why I feel very happy with that particular sequence in Tarang. It doesn't have, in any sense, an imitation of Eisenstein."

Kumar Shahani remains one of the directors in that rarely seen and even more rarely discussed group of filmmakers. That he was Kolkata for the last few years, very few knew about. He moved about silently. In retrospect, I think, I saw him in last year, June, in an Art Gallery in Park Street at a Shanu Lahari retrospective exhibition. But it did not dawn on me that it was Kumar Sahani. I could have gone up and met him. What bad luck! We have lost him. And we are going to lose his work. Unfortunately, neither are there home video releases for his films, nor are there widespread public screenings or film fest retrospectives within the country to generate interest. Heck, they don’t even make their way into the world of file sharing and peer to peer networks. We are now at a point where even the original negatives of the films face the risk of extinction.

Adieu!