Nothing much has changed in this 350 years, from Plague to Pandemic.

Nothing much has changed from 1665. People not wearing masks. Gathering in market place. Huge amount of policing required.

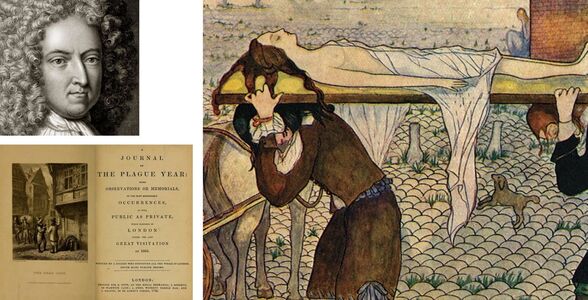

If we are to go by the accounts of Daniel Defoe in his book A Journal of the Plague Year, published in 1722 the situation is exactly the same. We all know Defoe from his book, Robinson Crusoe but his other book on the London plague is less known, initially because it did not have the name of the author but was published as : By a Citizen who continued all the while in London. Subsequently in 1780 edition was published with his name.

A Journal of the Plague Year is a book by Daniel Defoe, first published in March 1722. It is an account of one man's experiences of the year 1665, in which the bubonic plague struck the city of London in what became known as the Great Plague of London, the last epidemic of plague in that city. The book is told somewhat chronologically, though without sections or chapter headings, and with frequent digressions and repetitions. Presented as an eyewitness account of the events at the time, it was written in the years just prior to the book's first publication in March 1722. Defoe was only five years old in 1665 when the Great Plague took place, and the book itself in its preface had the initials H. F. and is probably based on the journals of Defoe's uncle, Henry Foe, who was a saddler and lived in the Whitechapel district of East London.

In the book, Defoe goes to great pains to achieve an effect of verisimilitude, identifying specific neighbourhoods, streets, and even houses in which the plague had massive effect. Additionally, it provides tables of casualty figures and discusses the credibility of various accounts and anecdotes received by the narrator.

The first thing to say about A Journal of the Plague Year is that it is not, strictly speaking, a first-hand record. It was published in 1722, more than 50 years after the events it describes. When the plague was ravaging London, Defoe was a small boy. Defoe claimed that the book was a genuine contemporary account – its title page states that the book consists of: “Observations or Memorials of the most remarkable occurrences, as well public as private, which happened in London during the last great visitation in 1665. Written by a CITIZEN who continued all the while in London. Never made publick before” and credited the book to HF, understood to be his uncle Henry Foe.

But that shouldn’t be taken too seriously: Defoe also claimed that Robinson Crusoe was written by a man who really lived on a desert island for 28 years, and that his book about the celebrated thief Moll Flanders was written “from her own memorandums”. He even put that claim in the latter’s title, which is worth recounting in full: The Fortunes and Misfortunes of the Famous Moll Flanders, Etc. Who was born in Newgate, and during a life of continu’d Variety for Threescore Years, besides her Childhood, was Twelve Year a Whore, five times a Wife (whereof once to her own brother), Twelve Year a Thief, Eight Year a Transported Felon in Virginia, at last grew Rich, liv’d Honest and died a Penitent. Written from her own Memorandums.)

This is not to deny A Journal of the Plague Year’s literary or historical significance. It’s possible that it was at least based on Defoe’s uncle’s journals. It is certain that Defoe himself did a lot of research into his subject, and used his considerable talents to bring it to life. It’s full of vivid descriptions of the way the plague moved through the different neighbourhoods of London, the precautions taken to fight it, and the chilling progress of the carts loaded with corpses accompanied by cries of “bring out your dead”. There are also remarkable insights into human behaviour under the shadow of a pandemic, not to mention instances of misbehaviour and madness, such as that demonstrated by a character called Solomon Eagle who took to parading about the streets off the Fleet, denouncing the sins of the city “sometimes quite naked, and with a Pan of burning Charcoal on his Head”, reminding one of the Bhakts coming out with different medicine from Cow Urine to Dung.

Defoe himself will also be an intriguing subject for us. As well as writing more than 300 books and tracts (some put the figure as high as 545) under almost 200 different pen names, he travelled widely, once ran a tile and brick factory, found time to take part in the disastrous Monmouth rebellion attempting to overthrow James II, and to make and lose several fortunes. At one time, he owned a ship and country estate; at others, he was held in debtors’ prisons. He also went to jail for pretending to argue in his 1702 satire The Shortest Way with Dissenters that the best way of dealing with religious rebels was to banish them abroad and send their preachers to the hangman. So many people failed to see the joke that the House of Commons had the book burned, put the author in Newgate prison, and then sent him to the pillory for three days. Defoe was also marched to a different set of stocks each day but, instead of rotten fruit, the crowds threw flowers at him while his friends used the opportunity to flog more of his pamphlets.

All that was before he really got going. His most famous book, Robinson Crusoe, came out in 1719 and A Journal of the Plague year followed in 1722. In his productive last years, he also wrote a huge travel book about Great Britain, the aforementioned Moll Flanders and more than a dozen other novels. Many of them were hits but at the time of his death in 1731, he was likely in hiding from creditors. Some life.

A Journal of the Plague Year is available for free on Project Gutenberg.

Image : Engraving of Daniel Defoe. First Edition of the book.

Illustration of the Great Plague of London,1665. By Kitty Shannon.