I had met Jayabroto Chatterjee occasionally on social gatherings and came to know him and his wife Subhra. Subhra was also involved with Indian Institute of Cerebral Palsy and we met for work, particularly on their drive to promote their New Year’s Greeting Cards.

I came to know Jayabrato Chatterjee more closely when I joined Ambuja Cements as the CEO to build the Heritage Park. Jayabrato was the Chief of Corporate Communication of the Group for Eastern India. And it is here that Jayabrato Chatterjee became ‘Jay da’ to me.

The company was fledging: Housing, Resorts, Heritage Park, Mall, Destinations, and City Centres. Jay da had his hands full. He brought Style, Elan and Grace to the communication befitting the group, particularly Harsh and Madhu Neotia.

A writer, filmmaker and a corporate communicator par excellence who had also directed films he came to look after the communication strategy of the group. He was one of the great all-rounders of his day, a man of tremendous energy and versatility who made a career from his passions. He wrote the copy, directed the shooting and designed. Only later did he advice that the group should move to a professional agency to handle the different accounts.

He had a team who were all very close and addressed all of them with a ‘tui’. There was more than a touch of Boy's Own about him. He was a glorious combination of idiosyncrasy and beautiful manners, all the time bubbling with vitality and gob-smacking gusto.

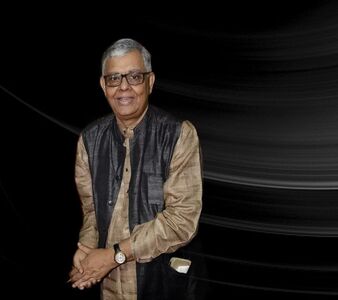

He wore the right clothes: invariably wore a smart Kurta, Pyjama mostly from FabIndia when they were not that popular. He had a passion for Jackets which he always wore. His Kurtas were immaculate. The overall impression was of a fashionplate from a bygone age. The sartorial fireworks fitted in very well with the highly eccentric literary style which made such a name for him when he published his articles.

The curious style came about by chance. Sometimes in 1980s, commissioned to write about custom cars, I think for Society magazine, Jayabrata got as far as writing hurried notes and told the editor, to give them to someone else because he could not produce the finished piece. The Editor read the notes and printed them as they were. The peculiar style, full of exclamation marks, words elongated for special effect, and words in capital letters, gave the impression of news that was too hot for the simple declarative sentence; also that it was highly complicated to explain but that Jayabrata himself knew all there was to know about it, and from the inside. As the news was from the counterculture or, later on, from the world of the Bombay new rich, the prose seemed to fit the passion.

Early on, he demonstrated his unusual angle on stories, and it was not always appreciated. Once he was sent to cover a concert of classical music in Kolkata and wrote a long piece about the way people sat on the grass listening to it. This confused the editor to no end. Another time he was covering an event at St. Xavier’s College and wrote mainly about how the president of the Debating Society of the college held his chin in a jut-jawed fashion while speaking.

Jayabrata has written a number of books. I have not read all but I liked the Soft Eclipse. It is the story of Mohini, a Bengali woman caught between the middle-class upbringing and the sheer shallowness and artificiality of upper-class Bengali society. It is the story of the majority of Indian women, one of sacrifices, compromises and love. Superbly written and laced with a fantastic sense of humour, the novel gives a scathing portrayal of Kolkata's corporate world of the 70s and also takes the reader behind the scenes of Kolkata's superficial high society to show the sexually disturbing and shockingly sad lives that they lived. Even though written by a man, it voices the interesting and mostly disturbing stories of many women in an authentic and brilliant manner. From love stories, family relationships and issues of religion, to the sex lives and illicit affairs of the characters, the novel has every element required to keep the reader interested till the last page. The other books are: Beyond All Heavens, Kolkata: The Dream City, Last Train To Innocence.

Jayabrata was born in Santineketan and moved to Dehradun at the age of four. He describes his days in Dehradun: My earliest memories were borne back in Dehradun (now in Uttarakhand), where I spent my childhood with my mother, Meera Chatterjee, my maternal grandmother, Kamala Bisi and my Jethu, Rathi Jethu (Bengali term for father’s elder brother), Rathindranath Tagore. Jethu was Rabindra Nath Tagore’s second child and eldest son. Those were the first eleven and most impressionable years of my childhood. I still remember the rattle of the Dehradun Express that would carry us back to our home in the valley, away from the bustle and noise of Calcutta (now Kolkata). Jayabrata was encouraged to write by his mother, Meera, and at nine, he tried his hand at biographies of Napoleon and Mozart.

He went to a private day school, Cambrian Hall in Dehradun and then to St Thomas' College, Dehradun where he edited the literary magazine. Later he graduated from St. Stephen's College, Delhi.

Jayabroto Chatterjee was a good man, a kind man, an erudite man, a humble man. A man of culture, laughter, insight, and joy.

Jayabrata Chatterjee was born on 7th October 1950 and died on 19th December 2022. He is survived by his wife, Subhra and daughter Shahana Chatterjee.