On this Valentine Day here is Derrida on LOVE. In an open interview on being asked his opinion on ‘l'amour ‘ by Amy Ziering Kofman , he was quite taken aback. She repeated, ‘Whatever you want to say about Love’. And then Derrida reconciled to say that you can’t ask me a question like this. Pose a question in a way I can answer.

Derrida makes the distinction between the 'who' one loves - their singularity - and the 'what' - the specific qualities of the beloved; then, he states that philosophy's most basic question - 'What is Being?' promotes the same sort of differential reflection: "is Being someone or something?" Fidelity, he states, is always threatened by this division - between the desire to be faithful to the other's singularity and the qualities that may not be as one once thought ...

In regard to identity and love, is the What really different from the Who and vice versa? Do we always stay the same or falling out of love is the result of the movement of life, of the desertion of What/ Who we were at a certain point, an evolution as to what we aspired to (“outgrowing someone”)?

“The difference between the who and the what at the heart of love, separates the heart. It is often said that love is the movement of the heart. Does my heart move because I love someone who is an absolute singularity, or because I love the way that someone is? (…)

That is to say, the history of love, the heart of love, is divided between the who and the what. The question of Being, to return to philosophy - because the first question of philosophy is: What is it “to Be?” What is Being? The question of Being is itself always already divided between who and what. Is ‘Being’ someone or some thing? I speak of abstractly, but I think that whoever starts to love, is in love, or stops loving, is caught between this division of the who and the what. One wants to be true to someone - singularly, irreplaceably - and one perceives that this someone isn’t x or y. They didn’t have the qualities, properties, the images, that I thought I’d loved. So fidelity is threatened by the difference between the who and the what.”

This love means an affirmative desire towards the Other - to respect the Other, to pay attention to the Other, not to destroy the otherness of the Other - and this is the preliminary affirmation, even if afterwards because of this love, you ask questions. There is some negativity in deconstruction. I wouldn't deny this. You have to criticise, to ask questions, to challenge and sometimes to oppose. What I have said is that in the final instance, deconstruction is not negative although negativity is no doubt at work. Now, in order to criticise, to negate, to deny, you have first to say "yes". When you address the Other, even if it is to oppose the Other, you make a sort of promise - that is, to address the Other as Other, not to reduce the otherness of the Other, and to take into account the singularity of the Other. That's an irreducible affirmation, its the original ethics if you want. So from that point of view, there is an ethics of deconstruction.

In the question and answer somebody asked him, “Did you fall in love with your wife the first time you met on the trip to the snow?” A question which he wouldn’t answer when we asked in the film. And to the surprise, he quickly responded, “Yes!” I’d fully expected him to avoid answering the question because it was too personal, and instead to spin it into something else. But he didn’t. Those moments have been pretty interesting to watch.

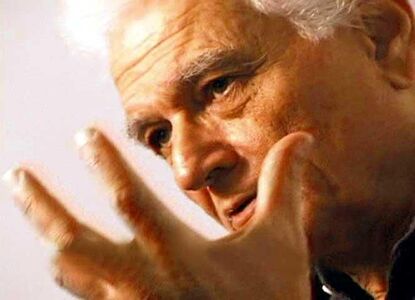

Jacques Derrida was a French philosopher, born in French Algeria. He developed a form of semiotic analysis known as deconstruction. His work was labeled as post-structuralism and associated with postmodern philosophy. He published more than 40 books, together with essays and public presentations. He had a significant influence upon the humanities, particularly on anthropology, sociology, semiotics, jurisprudence, and literary theory. His work still has a major influence in the academe of Continental Europe, South America and all countries where continental philosophy is predominant. His theories became crucial in debates around ontology, epistemology (especially concerning social sciences), ethics, aesthetics, hermeneutics, and the philosophy of language. Jacques Derrida's work also influenced architecture (in the form of deconstructivism),art, music, and art critics. Particularly in his later writings, he frequently addressed ethical and political themes. His work influenced various activists and political movements. Derrida became a well-known and influential public figure, while his approach to philosophy and the notorious difficulty of his work made him controversial.

Watch the original interview on YouTube: http://youtu.be/dj1BuNmhjAY