Gokhale being too rational and far-sighted did not arouse those deep, compelling and divisive passions essential to mobilise people and to keep narrow versions of nationalism alive.

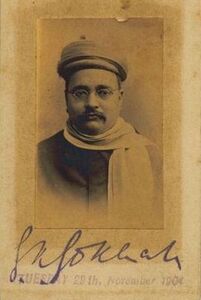

Commemoration in any form an appropriate moment to relate the past to the present and to reinterpret history. The 75 Years of the Gokhale Memorial School is good as any to remember the long-forgotten Gopal Krishna Gokhale.

In the current Indian political debate where Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Bhagat Singh, Jawaharlal Nehru, Mahatma Gandhi and B. R. Ambedkar are all competing for the status of makers of modern India, perhaps it would be necessary to sit back and look at what Gokhale – whom Mahatma Gandhi himself called his political guru – contributed to modern India

At first sight, it is very tempting to say that Gokhale’s ideas would not have any audience today and that, after all, Gokhale had simply internalised the hegemonic thinking promoted by the British as a justification for their imperialism, that is liberalism. In fact, Gokhale quoted Edmund Burke and John Stuart Mill; he believed that any activity had to be limited to the constitutional realm and that each step on the path of self-government, however small, was significant; he was wary of any ideology that mobilised the masses. So, it is quite easy to be convinced that the soft-spoken moderate leader was detached from the people’s issues and that he was no less elitist than the British colonisers.

Nevertheless, such impression is misleading. If it is true that Gokhale can be qualified a moderate for his commitment to constitutional methods, it should not be forgotten that he supported social and economic reform much more decidedly than other leaders who are even today saluted as national heroes.

For this purpose, a glimpse to Gokhale’s idea of the nation and his concept of independent economy can be useful to show that Indian liberalism was broader in scope than certain bold nationalism which was louder in attacking the British Raj.

The idea of the nation articulated by Gokhale was predicated on the concept that, from being a geographical unity well-delimited by the Indian Ocean and the Himalayan mountains, India had become a political unity, thanks to the administrative unification under the British rule. All the inhabitants of this space, all those people that have “come to make their home here [and] have brought their own treasure into the common stock” were Indians. Thus, Gokhale’s imagined nation was political, territorial and cultural, but it was the voluntaristic element – that is the individual consciousness of being part of a given nationality – the most powerful sentiment that made the nation capable of constituting itself and finally becoming independent. In other words, belonging to the same culture was not enough: in order to achieve national unity, what was crucial was the political will to participate to the well-being of the nation, to contribute to its progress and amelioration. So, the nation existed in the future, and not in a golden past.

Gokhale gave a bigger credit to the British for this unification to this larger concept of a politically unified India. It has become more important now in the present context of our understanding of a unified India irrespective of caste or creed; religion or belief ;party or politics.

It is imperative to emphasise that the future common project Gokhale envisioned for India was not only predicated on the fight against British imperialism, but also, and even more importantly, on social equality, without which neither progress – moral and material – nor freedom could be achieved. Then, the deep divisions and disabilities based on gender, caste and religion that characterised Indian social structure had to be overcome, or else conflict and uncertainty would prevail over peace and prosperity. It is towards this, Gokhale perceived the appallingly inhuman treatment of low castes by higher castes as worse than the treatment reserved by the British to their Indian subjects, both in India and in the white colonies.

In this context. what is more, Gokhale held that the need of education for women was even more urgent due to the fact that religious beliefs affected more women than men. Therefore, from being the doctrine which justified the British rule in India, liberalism was mutated into an instrument of dissent and resilience against that same rule and, significantly enough, against those ideologies that, in the name of social order and cultural authenticity, did not recognise any liberty to the single individuals, much less to women, the economically unprivileged and untouchables. In this sense, far from being a conservative system of thinking, such liberalism became a radical tool to defy the colonial order at the same time and to catalyse social transformation against the internal evils of the Indian society.

The establishment of the Servants of India Society in 1905 was the embodiment of Gokhale’s ideals and principles for the nation in the making: it was an effort to shift from the high political level to the grassroots level with his national project. The Servants of India Society was formed in Pune, Maharashtra, on June 12, 1905 by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, who left the Deccan Education Society to form this association. Along with him were a small group of educated Indians, who wanted to promote social and human development and overthrow the British rule in India. The Society organized many campaigns to promote education, sanitation, health care and fight the social evils of untouchability and discrimination, alcoholism, poverty, oppression of women and domestic abuse. The publication of The Hitavada, the organ of the Society in English from Nagpur commenced in 1911.

It goes without saying that Gokhale’s political idea of the nation did not consider the Indian nation as timeless given, a cultural fact. Antithetical to this vision was the cultural nationalist ideology which gave priority to the cultural commonality and did not attribute any relevance to the individual will to be part of the nation, since the latter existed a priori and could not be disputed. According to this romantic cultural nationalism, promoted by the leader of the Extremists, Tilak, and later on systematised by Savarkar, the only authentic Indian culture of the subcontinent was the Hindu one. Unfortunately, since Hindu culture, described as ancient, pure and characterised by permanent traits, was presented as the sole binding factor of the nation, the most logical consequence was an attitude of resistance against influences coming from other cultures. In a reality as diverse as India, such a vision of the nation could not but lead, besides to the obvious rejection of everything British, to the exclusion of the Muslim minority, regarded as one of the historical agents that had greatly contributed to the contamination and decline of the glorious (very often invented) Hindu past. Therefore, in this outlook, the nation became object of a sentimental and irrational adoration, since it embodied the essence of the civilisation of the Indian people. The main consequence of the revaluation and glorification of Hindu traditions was that Hindu values became ‘national’ values.

All this considered, it should not sound surprising that Tilak defined the liberal nationalism à la Gokhale ‘un-national’: according to him it was preposterous that different religious nationalities could be brought under the same polity and, in his opinion, the individual’s rights had to be surrendered to communities. Gokhale’s liberal ideology, supporting all-round liberties for the individual and advocating a juster society free from religious and caste prejudices, was attacked time and again by the extremists, because it jeopardised the ‘national’ identity in name of an ‘alien modernity’ (even though both the monolithic Hindu identity and the romantic concept of cultural nationhood were equally by-products of the same modernity). Yet, unluckily, taking up the cudgels against Gokhale and his reformist ideas implied, more or less directly, the persistence of dehumanising master-servant relationships continued and then the rejection of the chance of building a society fit for all Indians.

All in all, there were different and conflicting strands within the anti-colonial movement and, in contrast with what some historians maintain, some were religious, community-based and discriminatory. Patterns of inclusion or exclusion, democratic or undemocratic principles, equality or disability are to be found in Indian nationalism from its beginning: since late nineteenth century, intolerant and exclusionary ideas of the nation were organic in Indian political discourse as much as liberal ideas of the nation. The debate on the Education Bill, drafted by Gokhale and presented in front of the Imperial Legislative Council in 1911, is very telling of the contrasting social visions that characterised the national movement. In Gokhale’s view, universal, secular, free, and compulsory education was ‘the question of the questions’, because upon it depended the well-being of thousands of children, the increased efficiency of the individual, the higher general level of intelligence, the stiffening of the moral backbone of large sections of the community.

Though Gokhale eventually moderated the contents of his proposal for fear that it could be a source of division among the anti-colonial movement, the Education Bill met a great deal of opposition by many Indian leaders. Some criticised the bill because the kind of education it promoted was not based on religious identity and so it was not ‘national’; others fretted about the shortage of child labour, some others commented that children of poor classes and lower castes could become gentlemen. All these demanded a national education different from the one proposed by Gokhale, because the nation they envisioned was different: something which shows very clearly that anyone who was fighting against injustice by foreigners was not necessary fighting against injustice by Indians towards Indians.

An outcome of such thought is the founding of such institution as Gokhale Memorial Girls' College a premier educational institution in Kolkata offers both general and career-oriented education which is a reflection of its moorings in traditional values coupled with a modern approach to both teaching and learning. The institution endeavours to bring about the all-round development of the students by encouraging self-expression to draw out their latent capabilities. The College was initially established as an extension of Gokhale Memorial Girls' School in 1938 by Sarala Ray, popularly known as Mrs. P. K. Ray, a great social reformer and educationist. It gradually emerged as one of the premier educational institutions in India in its own right, imparting quality education to women and making them worthy citizens of a progressive nation. Its 75 year journey from 1938 has seen countless young women performing successfully in different spheres of life.

Now let us examine the important economic ideas of Gopal Krishna Gokhale. All of them still very relevant and contemporary in thought.

The first is the idea of Indian Finance: With regard to Indian Budget, Gokhale held the view that, it should be passed item by item. In such a case, people having sound knowledge of Indian conditions would get an opportunity to express their opinion on various items of expenditure. Suggestions made by non-official members should be referred to a committee of control.

Gokhale was not in favour of surplus budgets. He held that a policy of surplus budget was unsound. He believed that a surplus budget would demoralize even the most conscientious government for resorting to wasteful expenditure. He thought that a succession of surplus budgets would made the government indulge in extravagant expenditure. Something we are talking about today and reflected in the current budget.

He thought it would be, “Specially true of countries like India where public revenues are administered under no sense of responsibility, such as exists in the West, to the governed.” Gokhale was against using the budget surpluses for repaying the debt incurred for the construction of Railways. As the railways were a commercial undertaking, it should meet its debt commitments from its own income and not from the proceeds of taxation.Again , for the first time this has been highlighted in the current budget and underlined. An idea far ahead and which took 70 years for us to understand and implement.

The finances of the local bodies and provinces were poor. So Gokhale suggested an equitable distribution of tax revenue between the centre and provincial governments and local bodies. So he suggested that land revenue, excise and revenue from forests might be given to the provinces. Opium, salt, customs, post and telegraphs might be given to the Imperial government. The quinquennial revenue settlement might be given to the local bodies. Again an idea which was implemented in the last budget and the GST is a move toward this.

Gokhale was an advocate of decentralisation of power. He suggested the creation of panchayats at the village level and then local boards and district councils. He suggested the creation of a council of members in the provinces to assist the Governors. He held that the provincial legislation should discuss important matters relating to finance and the budgets.

In 1896, the British Government decided to increase the duty on salt to meet the deficit of 1.5 million pounds which arose as a result of the annexation of Burma. Gokhale opposed this as it would place a heavy burden on the poor. Again in 1879, the government removed the 5 percent import duty on textiles and in 1896 imposed 31/2 percent excise duty on Indian cotton goods. Gokhale attacked these two measures. The Pachayats were set up in

Gokhale was highly critical of large increase in public expenditure. He pointed out that India’s monetary resources were mis-spent in extending northern and north eastern frontiers and in using troops for imperial purposes. He charged that the British government was looking after the interests of British traders and it did not bother about the Indian tax payer. So he emphasised the need for controlling public expenditure in India.

A Royal Commission was appointed in 1895, “to enquire into the administration and the management of the military and civil expenditure, and the apportionment of charges between the government of the United Kingdom, and of India for the purposes in which both are interested.”

Gokhale was one of the non-official witnesses of this commission.

He divided his evidence into 3 parts:

The first one dealing with the machinery of control,

The second with the progress of expenditure and

The last portion dealing with the apportionment of charges between England and India.

Gokhale pointed out that in England and other countries, public expenditure was controlled by tax payers. But in India, there was no popular control over the public expenditure. The Indian tax payers had no voice over this matter.

With regard to progress of expenditure, Gokhale expressed the view that ever since the transfer of power from the East India Company to the crown, there was a tremendous growth of public expenditure. The average expenditure increased to Rs. 73 crores from Rs. 3 crores.

As far as the apportionment of charges between the United Kingdom and India was concerned, Gokhale suggested that the India office charges should be shared on 50:50 basis, the army charges should be paid by the crown, the public debt of India should be charged to the crown and the crown should pay a reasonable share of the cost of maintaining the British army stationed in India.

Gokhale suggested the following remedies to check the growth of public expenditure:

(1) The expenditure should be incurred with a spirit of economy. It should not be allowed to exceed the normal revenue except under conditions of war, famine etc.

(2) Military expenditure should be cut down and the size of the army should be maintained to the extent of Indian requirements.

(3) More number of Indians should be employed in public services. Indians should be paid salaries at same rate as were being paid to the Englishmen.

(4) The audit should be made independent. The audit report should be laid before the parliament so that effective criticism of the financial administration maybe possible.

Much of this idea has been implemented and executed.

Gokhale stated that an illiterate nation could not make any progress. So educational facilities should be extended to all in the country. The expenditure on education must be an imperial charge. Education must receive same attention as army and railways.

We can say that even though there is no idea of the nation intrinsically more legitimate or authentic than another, it is still true that these ideas can and must be judged by considering their social consequences in terms of peace, democracy and inclusion. In the same way as the thoughts on economy has been envisaged.

But then, why is Gokhale not one of the revered deities of the national movement pantheon? The nation envisioned by Gokhale was predicated on an idea, rather than on external symbols. And exactly this was its weakness: being too rational and far-sighted, it did not arouse those deep, compelling, and divisive passions which are essential to mobilise people and to keep narrow versions of nationalism alive.

For this very reason, ideas similar to the ones embraced by Gokhale are at a low ebb in today’s India: obviously they are neither instrumental in promoting the nationalist agenda, nor useful for captivating any vote-bank. Not only that. These rational, inclusive ideas are even stigmatised as ‘anti-national’ because they are threatening the ‘traditional’ ethos. Nevertheless, going by what happened to Narendra Dabholkar, Govind Pansare, and M. M. Kalburgi, and more recently to the students at JNU; however paradoxical it might sound, the less ‘national’ India is, the better it is going to be for the overall stability and welfare of the nation.