It was 1987 I was working in Ananbda Bazar Patrika. Nikhil Sarkar popularly known as ‘Sree Panth’ had just finished writing his book Metiaburujer Nawab and was contemplating illustrating it to make it interesting. I received a call summoning me to his desk. I went to meet me and he requested me to hunt for images of Wajid Ali Shah and Calcutta during that period. I was in a tizzy. Even after a through hunt I could lay my hands on the original Koran of Wajid Ali Shah’s grand father which the family had brought to Calcutta along with a fine painting of Wajid Ali Shah on mica. Over and above some stray engravings of the period. But these were not sufficient to illustrate the book. At best it could serve as some sort of reference for the illustrator. Ananada Bazar had a plethora of illustrator and I felt Nikhil Sarkar would commission one of them.

The next morning the scenario had changed . Sarkar wanted me to go over to the house of the most elusive painter of our time, Ganesh Pyne and convince him to to discuss the possibility of illustrating the book. Why me? I asked. There was Bipul Guha the then Art Director of the group. But it was found that none was close to the recluse artist. I had some relation as I had gone over to his house to meet him earlier when my father was alive,to collect some paintings. I tried best to wriggle out but the situation became worse when Sarkar confided with my boss Arup Sarkar and it sort of became official.

I reached the street where he resided Kaviraj Row and parked my car on the main road to trudge in. A dilapidated two storied mansion stood at the end where Ganesh Pyne lived. A faint voice , “who is it?” I tried my best to impress and introduced myself with a long CV starting from my father and ending with Anannda Bazar and Nikhil Sarkar. This was followed by a long silence and wait. A young lad, who I later learned was his nephew, opened the ground floor door leading to a small quaint room. I was totally unimpressed. Not a single painting in the room only a picture of Ramakrishna Paramhansa and a Bengali Calendar from a Homeopath Pharmacy.

After some time Ganesh Pyne came down a narrow staircase and I stammered the proposition. He stopped me short and inquired about my father. I updated him and he told me that he had first met him at Basanta Cabin where he sat with a cup of tea pouring over his new treasure of books from College Street. And there ended the conversation. He was a man of few words and chose to listen. I narrated the project and he politely refused saying that it would take years to complete the work. He underlined that his was a slow process and it cannot be hurried. I sank in my chair as I did not know what to say. I returned to office to give the news to ‘Sree Panth’ and it ended with a whimper that I am ‘useless’.

A few days later I returned to Pyne accompanied by another of my colleague Susanta Mukherjee, who said that he had worked many years before with Ganesh Pyne on animation film. Armed with all the references from home including the priceless Koran we reached the door of Ganesh Pyne. I showed him the entire collection. He was particularly interested in a book of Charcoal Indian Drawings edited and published by Ananda Coomaraswamy. He went on turning the pages of this book and at the end said that he will consider. Thus began the illustration of the book in charcoal,a seminal work unheard of in Indian publishing in 1988.

Ganesh Pyne brought to life the book. Wajid Ali Shah, the exiled nawab of Awadh, left Fort William in 1859. The British then pensioned him off to Metiabruz, a desolate tract of land near the ports at Garden Reach. The splendour of the king’s exile, his abundance of wives, the sudden efflorescence of paan and poetry have been well documented. Matia burj, the dome of earth, which existed before Wajid Ali Shah made his regal progress there, before a fine Lucknowi dust settled on it. The place was not going to oblige with melancholy relics of the nawabi era or strains of ghazals wafting in the air. It was left to Pyne to bring it to life.

With this I started my long relation with Ganesh da. He loved films, the theatre and the arts. He said that he had heard of a great film called Sholay. I got tickets in a shanty hall called Opera, as by then released in 1975 it was a re-run. Ganesh Pyne was elated. He loved films. The basic movement of 24 frames per second astounded him. After Ganesh Pyne left art college and was practically jobless for a while, he joined the studio of Mandar Mallik, a creative filmmaker of the 1930s. In his studio, Pyne drew innumerable cartoons whose obvious inspiration was Walt Disney. This left an indelible mark on his later work, where the grasshopper, the tiny bird, the lion and the monkey kept reappearing. It was this exposure that finally liberated him and helped him develop two important stylistic features - distortion and exaggeration which he used to explore the deep recesses of his fantastical imagination to create uncanny images of disquieting creatures.

Other than animation the other aspect that had a deep impact on Ganesh Pyne was his obsession with death. He could never forget his first brush with death, in the summer of 1946, when communal riots had rocked Kolkata. His family was forced out of their crumbling mansion. As he roamed around the city, he stumbled upon a pile of dead bodies. On the top was the body of a stark naked old woman, with wounds on her breast. No wonder then his paintings rarely has light backgrounds, and blue and black happens to be his favourite colours. Death also finds its way back into his canvas through different motifs. Working mostly in tempera, his paintings are rich in imagery and symbolism.

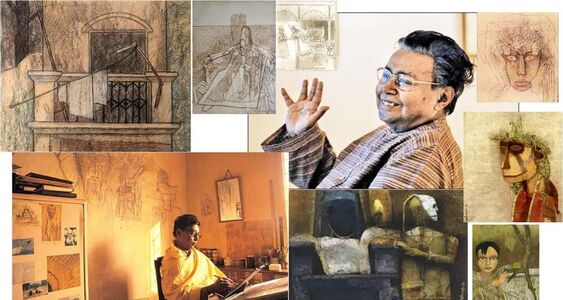

Pyne was born in 1937 and lost his father in childhood. He joined the Government College of Art & Craft in 1955 after an uncle was impressed with his ability to draw. He grew up on stories told by his grandmother --- ghost stories, mythological stories, and fairy tales. He spent evenings in Basanta Cafe in College Street discussing Communism and Picasso with his friends. "My childhood memories revolve around Kolkata. The sounds and smells of this city fill my being. I love Kolkata." He doesn't remember the first time he started to paint, but does remember the anger that he drew from his family over his decision to become an artist. Pyne, nevertheless, took admission in the Government College of Arts and Crafts, Kolkata. "My first painting was 'Winter's Morning' which showed me and my brother going to school," he recalls. In 1963, he joined the Society for Contemporary Artists. During that period he made small drawings in pen and ink. "I did not have enough money then to buy colour," Pyne says. This was also the period of experimentation. The anger and despair of the 70s fueled one of the most fruitful periods' in his life as an artist that culminated in works like 'Before the Chariot' and 'The Assassin'.

Initially, Pyne painted watercolors and sketches of misty mornings and wayside temples, variously influenced by the tradition of the three great Tagores— Rabindranath, Abanindranath and Gaganendranath. In 1968, he chose to work in the medium of tempera, which has now become synonymous with Pyne’s work. His paintings began to reflect the inner workings of his mind and he would revert to his childhood to dredge up images that lay concealed in his subconscious. The bedtime stories his grandmother often told him, and the oleographs and the image of Chaitanyadeb that he saw in a neighbouring Gauriamaths, surfaced in his paintings. This gave his temperas an intense poetic feeling as the images of death and decay are juxtaposed with those of the enchantment and richness of life.

Flowers bloom in a ribcage. Spring like a luscious maiden entices a skeletal ascetic.A queen converses with a mythical bird: half- man, halfbird.The twilight haze crackles with sinister eroticism. Pyne never churned out images but worked on each with the meticulousness of a skilled jeweller. Tempera is a very difficult process of painting. It is a permanent fast-drying painting medium consisting of coloured pigment mixed with a water-soluble binder medium usually egg yolk. His palette was quiet. Ambers, blues, greens and warm reds sing in a low key, suffusing the atmosphere with melancholy. His paintings glowed with the light of lamp stand led viewers into a fantasy land of terrifying beauty.At first it took time and he produced at an average one painting a year.He brooded over his work. Made sketches in the wall to save paper and then went about meticulously to depict the image.

Pyne suffered great privations in those early years as an artist. He painted ceaselessly but with great reservation and care. In retrospect, he felt that hardship and toil contribute to the growth of any artistic sensibility. Where others would have given up in despair, he went back to painting every evening for consolation. His signature style shaped from his own experiences of solitude, alienation, pain, horror and moods of tenderness and serenity comes to surface in each of his works. At times, these images are offshoots of an idea that may have flitted through his mind. At others, they resonate lines from poems that may have made an impression on his mind. I got a glimpse of this struggle when Ganesh da told me, “I’ve spent the last three-four nights chasing the image of Wajid Ali Shah but it just refuses to surrender to me!” The lines are bold, precise, controlled and the drawings that emerge are potent both in form and content. Stripped of colour, they convey the architectonic quality in the structuring of the images.

Ganesh Pyne loved the cinema He drew inspirations from movies made by Fellini and Ingmar Bergman. He was a regular at film festivals. Perhaps, he found the chiaroscuro of light and darkness spellbinding. The clowns, simple folks and the nomadic singers of Fellini and the black and white contrast of death and life of Bergman fascinating. Or perhaps they offered him a world of myths and folklores that attracted him since his boyhood. The walls of his studio became the screen of the cinema hall and are alive with his fascinating scribbles and doodles. Quite as fascinating as his notebooks that crawl with sketches and commentaries.

There is to be a literal que outside his home to buy his paintings. And some had to wait for years.Violin maestro Yehudi Menuhin had bought his painting. M. F. Husain put him at the top of his list of great contemporary artists of India. Indira Gandhi used to admire his work and when foreign dignitaries came to visit her, the Prime Minister would often choose a Ganesh Pyne from the National Gallery of Modern Art and put it up in her room. He was much sought after at international auctions. He consistently sold higher than many other Indian artists. Yet, paradoxically, his hauntingly beautiful paintings that opened charmed magic casements harked back to the stiflingly dark and cramped rooms of the century- old house in central Calcutta where he grew up.

Pyne fell ill a few years ago but recouped and continued to paint with renewed vigour. He worked on the theme of the Mahabharat and his last major exhibition was based on that theme. The world of the Mahabharat , where not a single character is blameless, continued to fascinate him, and he took up the theme recently once again.When asked about it's significance in this turbulent times he just smiled.Ganesh Pyne spoke very little and let his art do all the talking.

He was an incorrigible romantic. Rejected in love he never married. When the lady lost her husband, she returned to him and they married late in life. After his marriage, when he shifted from his ancestral house on Kaviraj Row to his wife's posh south Calcutta apartment, 20th century came to its close and he started living in a masonic cloister. He hardly met people except at public events. Still, we kept in touch over occasional telephone call not mobile. He never avoided my yearly meet on Bengali New Year’s Day just to hand over a gift of books and Bengali sweets. The last I met him was at Hyatt enjoying Sushi with his friend and family. He looked a little pale but seemed fine.

Very recently as I sat with my dear friend Sanjay Nigam discussing all subjects under the sun, the paintings of Ganesh Pyne came up and we fell silent. Such is our reverence for his work that a heavy silence prevailed before we went on contributing lines in praise of his work. This reached a crescendo where my friend confessed that he would love to have one of his paintings to admire, to stare day in and out. To make meaning of those fine intricate etchings. I remembered that many years back, my boss at Rediffussion, Subhas Chakraborty, had said the same thing.

The reclusive Ganesh Pyne, one of the greats of contemporary Indian art who held a mirror to his turbulent inner life in his crepuscular paintings, died of a cardiac arrest on the way to a private hospital in Calcutta on 12th. March morning. Death as the obverse side of life, and darkness and its complement light, were a constant presence in his work, and he avoided any direct political commentary. This was singularly marked as the hearse left the hospital to the crematorium accompanied by a handful of painters. No politician,no flag,no convoy,no followers,no slogans,no mourners only the dense dark silence that preceded and followed it. A scene straight out of Bergman's Seventh Seal.

I was out of town in a small village named Dumkal in Murshidabad and the news did not reach me. Today morning I picked up the papers and on reading,knelt down to the floor and started to weep.