It seems that the Bengalis are much more happy with Bob Dylan being named the surprise winner of the Nobel prize in literature “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”.

Many argued against the award, as they argued against him in the long and infinitely tiresome Dylan v Keats controversy, and as others have contested the meaning and value of every phase and nuance of his output. Others felt that he does not deserve the Nobel Prize simply because what he wrote were lyrics not poetry.

But the Bengalis went gaga as they were already used to it. Their very own Rabindranath Tagore who reshaped Bengali literature and music, as well as Indian art with Contextual Modernism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries also authored Gitanjali and its "profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful ", to become the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913.

Gitanjali or Song Offerings is a volume of lyrics rendered into English by the poet himself, was first published in 1910, Tagore’s collection Gitanjali, Song Offerings of mystical and devotional songs was translated to English in 1912. It would be the first of many volumes that earned him much acclaim in the East and West.

It includes an Introduction by fellow Nobel prize-winning poet William Butler Yeats; These lyrics...which are in the original, my Indians tell me, full of subtlety of rhythm, of untranslatable delicacies of colour, of metrical invention—display in their thought a world I have dreamed of all my live long. Some written in colloquial language and many with themes of naturalism, mysticism and philosophical insight.

My taste for music was somewhat different. I had listened to Bob Dylan but thanks to my musician son, Abhishek, who had introduced me to the songs of Bob Dylan and over time I grew a liking for his poems. In 2010 he presented me a book : Bob Dylan Lyrics 1962-2001 and I went through every word to declare him a poet , very near to my heart.

In May 2011 I first posted in facebook that Bob Dylan should be awarded the Nobel for Literature. Most of my friends laughed. Some made digs quoting him that he himself sees himself as a trapeze artist and a song writer. I continued with my campaign , writing to many of my media friends abroad and so the news did not take me by surprise that Dylan becomes a Nobel Laureate . Abhishek, I still have Dylan's book of poems which belonged to you.

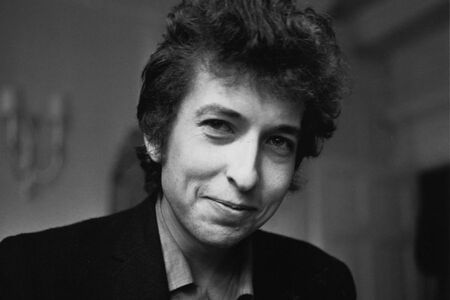

For more than six decades Dylan remained a mythical force in music, his wailing cat in the rain voice and poetic lyrics musing over war, heartbreak, betrayal, death and moral faithlessness in songs that brought beauty to life’s greatest tragedies.

In the latest of many distinctions garlanding a career stretching back five-and-a-half decades, Bob Dylan has become the first member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame to win the Nobel prize in literature. Others feel that he does not deserve the Nobel prize simply for being Bob Dylan, however that condition is defined. Pop lyrics aren't literature?

So, to confront the familiar argument, can what he does be called literature? And if he is being judged on literary grounds, should Tarantula, his “novel” of the mid-60s (started and abandoned in 1965, widely bootlegged and finally published officially in 1971), be taken as evidence? His fans know the first line by heart – “Aretha / Crystal jukebox queen of hymn & him” – but few reached the end. There was no music, as Dylan himself must have realized when he set it aside.

Essentially, in the work of Bob Dylan, the words and the music cannot be separated. Just take your favourite Dylan line. Yours might be the ever timely “Where preachers preach of evil fates / Teachers teach that knowledge waits / Can lead to hundred-dollar plates / Goodness hides behind its gates / But even the president of the United States / Sometimes must have to stand naked”, from It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) in 1965. Or the eternal “Ain’t it just like the night to play tricks when you’re trying to be so quiet?” (Visions of Johanna, 1966) or the mysterious “There must be some way out of here, said the joker to the thief(All Along the Watchtower, 1968). Whichever it is, when you say them to yourself, as we all do in times of need, you’ll be hearing his voice, his sound, his music.

Mine – at this moment, anyway, because the choice is bound to change from time to time when the library is so vast and rich – happens to be from The Times They Are A-Changin'

Come gather 'round people

Wherever you roam

And admit that the waters

Around you have grown

And accept it that soon

You'll be drenched to the bone

If your time to you

Is worth savin'

Then you better start swimmin'

Or you'll sink like a stone

It became anthemic for the 1960s, encapsulating the atmosphere of protest and change that surrounded the civil rights movement as well as the campaign to end the war in Vietnam. Over the span of his 50-year career he has sold over 100m records, and was even given a special citation by the Pulitzer Prize committee in 2008.Strange how people who suffer together have stronger connections than people who are most content.” This is not “literary”, or poetic by his former standards. There is no “midnight’s broken toll” or “geometry of innocence”. Dylan phrases it so perfectly in a single breath that the meaning is rendered starkly and with profound resonance. That’s what he does.

The admirable delicacy of the Nobel committee’s citation – “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition” – will certainly have provoked a buzz among analysts of Dylan’s career. For one thing, the last two albums released by a man now in his 76th year consisted entirely of material drawn from what has become known as the Great American Songbook: compositions by the very Broadway tunesmiths, in fact, who Dylan the songwriter seemed in the eyes of his own generation to have been invented to destroy. Dylan, however, has always been fond of turning his own iconoclasm on the idea of iconoclasm itself, his protests against being called a protest singer just one example of that refusal to conform to even the freshest of stereotypes.

Similarly, he never wanted to tear down the walls of Tin Pan Alley. That was an inference drawn by others, useful in the early phase of his career, when he drew from what he had heard in the collection of antique songs on Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music – the ballads, the bauls and blues, the music of hard times – and somehow infused it all with the onrushing anti-authoritarian, anti-deferential spirit of his own era.

As the Nobel citation correctly suggests, Dylan knitted himself – without anyone realising it, perhaps even him– into the warp and weft of American popular music. Borrowing wholesale from the past, reshuffling melodies, images, characters and attitudes, he helped assemble the components of a rapidly changing present.

Fifty years ago he used a fairly minor motorcycle accident as an excuse to step away from the spotlight. But the end of the “perfect” Dylan – the one who fused what he had learnt from Woody Guthrie and the symbolist poets with the energy of rock’n’roll, and who mocked the world from behind impenetrable shades – did not mean the end of his creativity. In songs such as Tangled Up in Blue (1975), Blind Willie McTell (1983) and Cross the Green Mountain (2002) he explored ways of playing games with time, voice and perspective, continuing to expand the possibilities of song in ways that deserved praise.

But Bob Dylan’s place as one of the world’s greatest artistic figures was elevated further on Thursday when he was named the surprise winner of the Nobel prize in literature “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”.

After the announcement, the permanent secretary of the Swedish Academy, Sara Danius, said it had “not been a difficult decision” and she hoped the academy would not be criticised for its choice.

“We hoped the news would be received with joy, but you never know,” she said, comparing the songs of the American songwriter to the works of Homer and Sappho.

“We’re really giving it to Bob Dylan as a great poet – that’s the reason we awarded him the prize. He’s a great poet in the great English tradition, stretching from Milton and Blake onwards. And he’s a very interesting traditionalist, in a highly original way. Not just the written tradition, but also the oral one; not just high literature, but also low literature.”

Though Dylan is considered by many to be a musician, not a writer, Danius said the artistic reach of his lyrics and poetry could not be put in a single box. “I came to realise that we still read Homer and Sappho from ancient Greece, and they were writing 2,500 years ago,” she said. “They were meant to be performed, often together with instruments, but they have survived, and survived incredibly well, on the book page. We enjoy [their] poetry, and I think Bob Dylan deserves to be read as a poet.”

Born Robert Allen Zimmerman in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1941, Dylan got his first guitar at the age of 14 and performed in rock’n’roll bands in high school. He adopted the name Dylan, after the poet Dylan Thomas, and, drawn to the music of Woody Guthrie, began to perform folk music.

He moved to New York in 1961, and began performing in the clubs and cafes of Greenwich Village. His first album, Bob Dylan, was released in 1962, and he followed it up with a host of albums now regarded as masterpieces, including Blonde on Blonde in 1966, and Blood on the Tracks in 1975.

He is regarded as one of the most influential figures in contemporary popular culture, though his music has always proved divisive. Speaking last year, Dylan said: “Critics have been giving me a hard time since day one.”

His own response to receiving the prize is unknown. He rarely gives interviews, and has a troubled relationship with the fame attached to his decades of popularity. However, he has toured almost non-stop since 1988 and last weekend he played the inaugural Desert Trip festival in California, alongside other giants of the 1960s, the Rolling Stones, the Who, Paul McCartney and Neil Young.

Only last Thursday night, the Chelsea theatre in Las Vegas saw the master songwriter gives his first concert since winning the Nobel accolade. Newly-minted Nobel laureate Bob Dylan kept cool as a cucumber on stage in Las Vegas, barely speaking a word to the audience in his first public performance since winning the coveted prize. As the audience chanted for more songs, Dylan gave just a brief encore, ending his set with a mournful yet playful cover of Frank Sinatra’s Why Try To Change Me Now.

Dylan’s lyrics had been an inspiration to me all my life ever since I first heard a Dylan album at school.

The frontiers of literature keep widening, and it’s exciting that the Nobel prize recognises that. I intend to spend the day playing Mr Tambourine Man, Love Minus Zero/No Limit, Like a Rolling Stone, Idiot Wind, Jokerman, Tangled Up in Blue,Blowing in the Wind and It’s a Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall.

Goodnight.