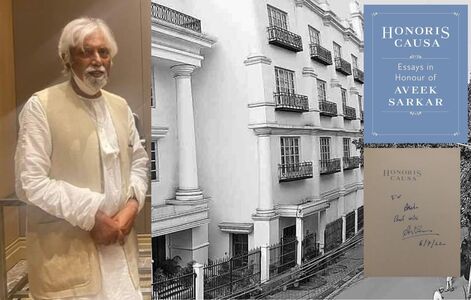

On the Eve of the 40th anniversary of The Telegraph, went to meet Aveek Sarkar. He has aged, but has not lost the razor sharp mind.

Giant among imaginative media promoters of the ideas of inter media progress, the occupation in different media and the urgent need for communication, Aveek Sarkar’s exploration is pre-eminent because of his hard and accurate predictions of the detailed technologies of communication and of the use of satellite for global communications.

Tallish, bespectacled, rather big-eared and a thinning hairline from age, he is beaming and highly articulate, erudite of a man to whom convention means very little. Yet his mind is sharp like a razor. Unlike earlier meetings, his imagination and creativity sprang, not from reality, but from sharp scientific and technical insight, unfettered by the arbitrary limitations of the perceptions of our time.

Aveek Sarkar's amazing career is possible largely because he is never, in any ordinary sense, quite a part of this world. Indeed he chooses to live in a world of communication, because it helps him neutralise the influence of everyday culture.

As he approaches 80, it seems that he has done almost everything that is possible in a single lifetime, for he has edited two mainline newspapers: Anandabazar Patrika and The Telegraph and for some time Business Standard which was his passion. He has launched several TV Channels and now involved in Anandabazar Digital. Through the several magazines which he oversaw he plumbed the depths of the wide readership spectrum, carried the imagination of many writers to the remotest parts of the country, and gained honours in every corner of the globe. But he now declares that one of his many remaining ambitions is to observe the meeting of urban and rural readership in a much wider form.

This spells out the technical case for the use of the satellite as a close and exciting reality: it embraces aspects of a new philosophy - in many ways Sarkar's lifelong philosophy - that sprang from the perceived and enormous spiritual need for a literate world, of a new kind which, by their magnitude and imagination, might hold mankind together.

Sarkar's stature and impact is probably greater than he could have imagined, as detailed by Nicholas Coleridge in his book: Paper Tiger: Sarkar’s influence starts from the Bay of Bengal and stretches to the South China Sea. It is certainly been far greater than that accorded by popular acclaim, for he is highly and, sometimes, effectively critical of the limitations of the spread of the printed word. He always sought and fought for new bridges between cultures.

This underlying seriousness has led him to view his participation in the digital medium, if poetic, other-worldly enterprises, as a kind of scenario writing, not to be taken as an example of his central work in print. In this, however, many would disagree, for Anandabazar Digital has reached a stature. Sarkar's ability is unique. He has the kind of mind of which the world can never have enough, a composite of imagination, intelligence and knowledge that is driven by great energy and a quirkish and unceasing curiosity.

Aveek Sarkar today is more concerned with the future of media. He is trying to shake the last vestiges of the printed word from his imagination, freeing his curiosity to probe the deepest recesses and allowing him to isolate and examine human relationships and emotions. I think that it is here, in the vastness and extraordinary beauty of technology that after a lifetime of confinement by printed word Sarkar will finally rediscover his own self.

This was evident earlier as expressed to Edwin Taylor, who was his design Guru at the Sunday Times, London and whom he brought to Calcutta to design The Telegraph, by his increasing belief in the use of communications to bring mankind together in what he called the "global village", the term borrowed from Marshal McLuhan, a dream that satellite communications would promote understanding and worldwide peace. By this time, however, it was clear that, as with any other technology, the effect of communication satellites depends entirely on their manner of use. The coverage of the Falklands campaign of 1982 and Operation Desert Storm, the American-led liberation of Kuwait from Iraq of 1990-91, showed clearly that global TV, rather than bringing mankind together in peace, can transform the horror of war into exciting and technically interesting family entertainment.

It was never evident that this reality soured the dreams that had driven Sarkar for five decades, for he never lost either his smile or his enthusiasm.

Certainly, Sarkar's imagination is magical, carrying him beyond the limits of possibility: his greatness is and remains that, from his almost Olympian heights, he could see more than ordinary men will ever see. Moreover, he possesses the power to carry anyone who wished to join him on these great heights of communication.