The uncle and nephew pair of Thomas and William Daniell landed in Calcutta 200 years ago and, for seven years, explored India as few others before them had done. Their sketches and paintings encompass all that is picturesque in the country, from the ghats of Varanasi to the waterfalls of the south. This is the story of their discovery of India

It was the year 1786. Calcutta had vet to become the second city of the British Empire and the “Kiplinges-que“ city of dreadful night." The East India Company had transformed the three sleepy villages along the delta of the Hooghly into a rapidly growing centre of trade and commerce with an increasing European population. Into this milieu, on a nippy January morning, arrived Thomas Daniell and his nephew William, sketchbook in hand and the artist's wherewithal for baggage. They were also on a conquering mission. But the only difference is that through their sketches, watercolours and acquaints they managed to capture not land and treasures but the essential ethos of eighteenth century India. Today, 200 Years later, the empire is gone but their work endures. The uncle and nephew had approached Calcutta across the Bay of Bengal and up the Hooghly River, delighting in the lush vegetation of the delta. They had set sail from Gravesend on 7th. April, 1785. On board the East Indiaman, Atlas, bound for Canton. At this time, the Company's most lucrative trade was with China and it was by no means easy to secure a direct passage to India. Many travellers were thus forced to sail to China, and then find a country ship that would escort them to India. This was the course that the Daniells followed.

Thomas Daniell was born in Kingston-on-Thames in 1749. His origins were humble: his father was Lessee of the Swan Inn at Chertsey. Thomas began his career as a hod-boy, assisting his brother, a bricklayer, by carrying bricks on a trough. Thomas would have become a bricklayer too, had it not been for the sagacity of his parents, who, sensing his discontent apprenticed him in 1763 to a coach builder. This was a job that interested Thomas, as it required a sense of colour. Moreover, it required a thorough knowledge of paints and varnishes, which was to stand him in good stead later. In 1770, after completing his apprenticeship, he worked for several years with Charles Cotton, then coach painter to George III and later founder member of the Royal Academy. Not merely satisfied with the painting of coaches, Thomas soon turned to painting watercolours. In 1772, he exhibited a painting depicting flowers at the Royal Academy and the next year, entered the Royal Academy School and proved his worth by having his paintings accepted by the committee of the Royal Academy year after year. This was no mean achievement, considering the fact that painters such as Joshua Reynolds, Gains-borough, Sandby, Romney and Copley were the established artists of that time.

Thomas sought permission to go to India as "an engraver." The self-description in his application is intriguing, for it is unclear how much experience he had had in the technique. There was, at that time, a lively interest in the new technique of 'aquatints' which had been introduced to England by Paul Sandby nine years ago. This was the art of engraving on copper with resin and nitric acid. Thomas had probably begun to experiment with this medium. The pro-cess had great possibilities for the landscape artist. It was common knowledge that there was a great shortage of engravers in the Indian Presidency towns, and Thomas may have felt that the profession guaranteed a secure income in Calcutta; in fact, he may have already hit upon the idea of producing a series of engravings of Indian subjects. On the other hand the form of his application may have merely been a prudent device to gain permission from the East India Company to go to Calcutta. A short while after submitting his own application, he also sought permission to take with him as his assistant his nephew William, then 15, who had begun to help him with his paintings in London. Thomas had adopted his nephew primarily to share in the family responsibilities. His brother, who had succeeded their father as landlord of the Swan, had died in 1779 leaving behind a widow who was continuing the business but was nevertheless finding life difficult with five children to look after.

On 1st December, 1784, Thomas' application was approved by the Court of Directors and. 10 days later, permission was given for his nephew to accompany him. All was now ready for the Daniells to depart for Calcutta. Throughout the eighteenth century the British settlement had been rapidly expanding in Calcutta and, by the end of the century, many painters based there were making a name for themselves in canvasses dealing with Indian subjects. Zoffany, Tilly Kettle, John Aldfounder, Samuel Andrews, Thomas Hickey, Diana Hill. William Hodges, Charles Sherineff and John Smart were all in India. Apart from the last named, who was in Madras, and Zoffany and Hickey, who were shortly to leave for England, the rest were based in Calcutta. Most of their work was in oil, but they also produced engravings and acquatints. To supplement these activities, many of the British residents employed Indian artists and by the late eighteenth century, Mughal painters from Patna and Murshidabad had also drifted to Calcutta. They were influenced by western techniques and began to paint in a half-Indian-half-British style. These artists came to be termed 'Company artists.' Their pictures, which depicted native costumes, occupations and festivals, appealed to both Indians and Europeans and were sold at nominal rates. Indian artists were also engaged by the British to paint birds and wildlife. In the late eighteenth century, Sir Elijah Impey, Mrs Wheeler and Nathaniel Middleton were all recruiting Indian artists to record local flora and fauna. Wellesley, the then Governor-General, also employed Indian artists to paint plants, animals and fishes. From 1793, many such artists began to visit the newly-established Botanical Gardens at Sibpur. Though such appointments were for specific purposes, the artist employed often made several reproductions to earn money. Such Paintings found regular buyers among the 'new babus' or Anglicised Indians. Moreover, the high death rate and constant movement of British personnel resulted in the frequent sale of such articles. Most were bought by other Europeans but at least a portion passed into the hands of Indians. Thomas Daniell was to write to his friend. Ozias Humphrey, in 1788: "The commonest bazaar is full of prints and Hodges' Indian Views are selling by cartloads."

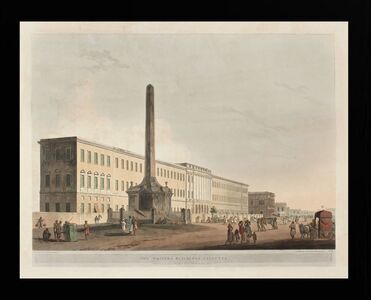

The Daniells found Calcutta a grand subject. Soon after settling down, Thomas inserted an advertisement in The Calcutta Gazette announcing his intention to publish a set of 12 views of Calcutta for 12 gold mohurs for sub-scribers. Thomas worked hard on the project and completed the series in 1788. These were some of the earliest street views of Calcutta. But, as Thomas himself recorded, his first major work in India, though it earned him fame, gave him "much fatigue and no profit." The art of acquatint, which was new in India, attracted Thomas. He and William began work on these Calcutta paintings using such a method. The series came up to the mark in terms of painting, but had grave printing defects. Thomas was not happy with this, and wrote to an artist friend in England, "It will appear a very poor performance in your land, I fear. You must look upon it as a Bengalee work. You know, I was obliged to stand painter, engraver, copper-smith, printer and printer's devil myself." Nevertheless the work is truly representative of the Daniells, for not only did they do all of the work themselves, but it also proved to be one of the finest recordings of a people in their native milieu. Each of the prints were 20.5 x 17.75". The 12 views were: Front Street, Old Mayor's Court, The Old Great Tank, Cheringhee, The River, Old Court House, The Esplanade, Government House and St John's Church. The complete set then cost 12 mohurs, and was sold in London for £24 as late as in 1939. Such views of the city were not new. William Baillie had already issued a set of 12 coloured views of Calcutta in 1784. The size of these paintings was 18 x 24" and they were sold in London for a mere £12 in 1936. Even after the Daniells, artist’s continued to make prints of Calcutta. James Baillie Frazer issued a set of 24 coloured lithographs titled Views of Calcutta and its Environs in 1826. The engraved surfaces were 16.75 x 11" and they were sold for £35 in London in 1939. In 1883, William Wood issued 28 hand-coloured lithographic views of Calcutta. Their size was 14.5x 18.5" and they were issued in five parts. One such set was sold for £18 in London in 1936. Charles D'Oyley published another set titled Views in Calcutta and its Environs in 1848, it comprised 27 coloured lithographic views, the largest measuring 33 x 13.5" and the smallest, 11 x 7.5". One such set was sold in London in 1939 for only £24. Despite the presence of so many other artists, the Daniells were immensely popular. Now, of course, the prices of their prints have skyrocketed. The production of acquatints, however, was slow work. The Daniells, in order to support themselves, were obliged to accept miscellaneous routine work such as the repair and cleaning of oil paintings of both private individuals as well as the East India Company. Though William Daniell had come along as a companion and as an assistant, he quickly learnt painting and even mastered the art of making acquatints. In later years, he himself recorded on canvas many of his impressions of the country.

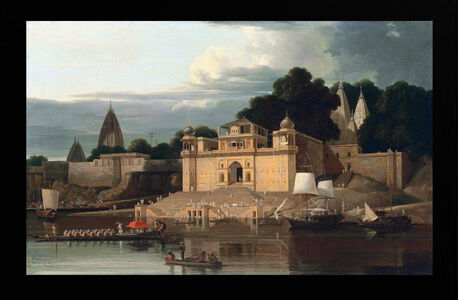

Meanwhile, the strain of the two years of hard work that went into producing the 12 views of Calcutta told heavily on Thomas' health. Afloat on a country boat on the Ganges. Thomas, writing to a friend, observed: "The fatigue I have experienced in this undertaking has almost worn me out ...It was a devilish undertaking, but I was determined to get through it all events." Doctors advised him to take a leisurely upcountry trip. So on 29th August, 1788, uncle and nephew set off on their grand painting expedition of India. It lasted for three years and covered practically all the important cities and pilgrim sites of India. It was a period of ceaseless travel and meticulous painting. It should be observed that the Daniells often made use of what was then known as the 'camera obscura' technique. A forerunner of the photo-graphic camera, this was a device for tracing images, consisting of a box set in a bellows, with one side open, over which a curtain was hung. It had a convex lens at one end and a small, adjustable mirror at the other, which threw an image upon a sheet of paper placed at the base of the box for the draughtsman to trace the outline. The Daniells returned to Calcutta in the autumn of 1791. On January 5, 1792, The Calcutta Gazette announced a lottery of the original paintings of Thomas and William Daniell, which they had done on their recent tour of the country. As many as 150 of their works were put on display in the rooms of the Old Harmonic Tavern in Lalbazar. On 1st.March the draw took place. The lottery attracted a large crowd although, as young William wrote to his mother later people were more ready to admire uncle's paintings than to buy them." The Daniells finally departed from India in late 1793, arriving in England on September 7, 1794.

In London, they hired rooms at 37, Howland Street, Fitzroy Square, and immediately launched upon their long-cherished project of publishing their monumental work, to be called Oriental Scenery. The work, started in 1795, was completed in 1808, and is a fabulous collection of acquatint views of Indian scenes. It is divided into six parts, each containing 24 assorted views. These were issued in elephant folios and the engraved surface of each plate was 24 x 18". An octavo-sized volume of text was also issued with each volume. The complete set was priced at only Rs 2,000 in 1937. In 1975, it was sold at an auction at Sotheby's for Rs 1,00,000. The last copy to be imported to India was in 1961, by KUMARS Antiquarian, Calcutta, ‘at a cost of Rs 20,000.

Thomas Daniell's next major work, A Picturesque Voyage to India by Way of China, containing 50 folio acquatints in small folio size was published at a price of £12.12 in London in 1810, but was available in 1933 for only £8. Today, when a complete set of Oriental Scenery appears, it is eagerly snapped up by Daniell connoisseurs. The Victoria Memorial, the collection of the Maharajah of Burdwan, both in Calcutta and the National Gallery of Modern Art in New Delhi contain original Daniells. In England, the Royal Institute of British Architects in Portland Place has six original large folio volumes of Daniell drawings, originally priced at £210 only. Another collection was offered for sale by Sir Henry Russel, and was acquired by Messrs Walker, of Old Bond Street, London. There are also some personal collections of Daniell engravings in Calcutta. Though none of them are complete, most are being built up, often concentrating on a particular region or place. Thomas Daniell was honoured by the Royal Academy, which elected him a full Royal Academician in 1799, soon after he returned home from India. When Oriental Scenery was completed the Royal Academy decided by unanimous vote to purchase a complete set.

After this, Thomas Daniell led a retired life and only painted sporadically. Between 1772 and 1830, he exhibited 125 landscapes at the Royal Academy, and ten at the British Institute. The only other not-able work that he completed, apart from his works on India, was Views on Egypt. Thomas Daniell died, almost forgotten, on 19th. March, 1840, at the age of 91 at Earl's Terrace, Kensington. His nephew, William, had helped his uncle complete Oriental Scenery. He also made independent trips of Britain to record his impressions. Thereafter, he broke away from his uncle and worked independently. From 1802 to 1807, he made extensive tours of the north of England and of Scotland, which resulted in many of his mature works. Among his principal works are, A Hindoo Temple Erected in Melchet Park (1802), Interesting Selections From Animated Nature (1807), Views of London (1812), Views of Bhootan (from the drawings of Samuel Davis, of the East India Company, who had visited Bhutan in 1783; 1813) William Daniell started work on Voyage Round Great Britain in 1814 and completed it in four volumes in 1825. Apart from these, he also painted a series with E.T. Parris titled Panorama of Madras and later, another series titled The City of Luck-now and the Mode of Taming Wild Elephants. Between 1795 and 1838, he exhibited as many as 168 pictures at the Royal Academy and 64 at the British Institute. He was elected Royal Academician in 1823 and died on August 16, 1837, at New Camden town, three years earlier than his celebrated uncle.

Thomas and William Daniell were perhaps no geniuses but, as their biographer Thomas Sutton, has observed. "They had sufficient talent and application to take an honourable place among their fellow artists." One thing that cannot be denied is that they were totally sincere towards their medium. Each subject they painted, be it a Calcutta street or the caves at Salsette, was depicted with unfailing critical observation. They had an acute sense of observation and insight. Paying a posthumous tribute to Thomas Daniell, the Calcutta Monthly Magazine commented," (from the paintings) one may almost feel the warmth of the Indian sky, the water seems to be in actual motion and the animals, trees and plants are studies for naturalists."

Photographs: KUMARS Antiquarian