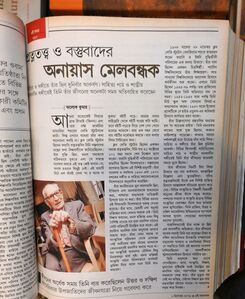

Whenever I take the name of Lévi-Strauss, out comes the retort: Off course I know Levi Strauss the German-born American businessman who founded the first company to manufacture blue jeans.

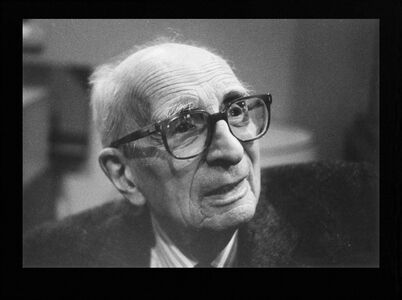

But I am talking of Claude Lévi-Strauss the French anthropologist and ethnologist whose work was key in the development of the theories of structuralism and structural anthropology. He died recently on 30 October 2009.

Lévi-Strauss argued that the "savage" mind had the same structures as the "civilized" mind and that human characteristics are the same everywhere. These observations culminated in his famous book Tristes Tropiques (1955) that established his position as one of the central figures in the structuralist school of thought. As well as sociology, his ideas reached into many fields in the humanities, including philosophy. Structuralism has been defined as "the search for the underlying patterns of thought in all forms of human activity.

Gustave Claude Lévi-Strauss was born in 1908 to French-Jewish, parents who were living in Brussels at the time, where his father was working as a portrait painter. He grew up in Paris, living on a street of the upscale 16th arrondissement named after the artist Claude Lorrain, whose work he admired and later wrote about. During the First World War, from age 6 to 10, he lived with his maternal grandfather, who was the Rabbi of Versailles. Despite his religious environment early on, Claude Lévi-Strauss was an atheist or agnostic, at least in his adult life.

From 1918 to 1925 he studied at Lycée Janson de Sailly high school, receiving a baccalaureate in June 1925 (age of 16). In his last year (1924), he was introduced to philosophy, including the works of Marx and Kant and began shifting to the political left. However, unlike many other socialists, he never became communist. From 1925, he spent the next two years at the prestigious Lycée Condorcet preparing for the entrance exam to the highly selective École normale supérieure. However, for reasons that are not entirely clear, he decided not to take the exam. In 1926, he went to Sorbonne in Paris, studying law and philosophy, as well as engaging in socialist politics and activism. In 1929, he opted for philosophy over law, which he found boring and from 1930 to 1931, put politics aside to focus on preparing for the agrégation in philosophy, in order to qualify as a professor. In 1931, he passed the agrégation, coming in 3rd place, and youngest in his class at age 22. By this time, the Great Depression had hit France, and Lévi-Strauss found himself needing to provide not only for himself, but his parents as well.

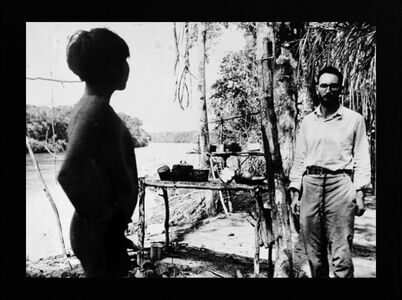

In 1935, after a few years of secondary-school teaching, he took up a last-minute offer to be part of a French cultural mission to Brazil in which he would serve as a visiting professor of sociology at the University of São Paulo while his then wife, Dina, served as a visiting professor of ethnology.

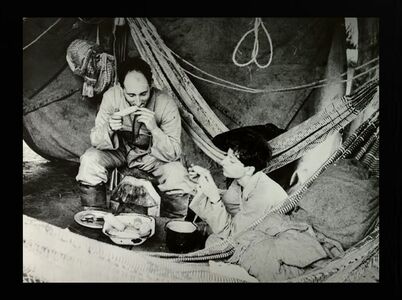

The couple lived and did their anthropological work in Brazil from 1935 to 1939. During this time, while he was a visiting professor of sociology, Claude undertook his only ethnographic fieldwork. He accompanied Dina, a trained ethnographer in her own right, who was also a visiting professor at the University of São Paulo, where they conducted research forays into the Mato Grosso and the Amazon Rainforest. They first studied the Guaycuru and Bororó Indian tribes, staying among them for a few days. In 1938, they returned for a second, more than half-year-long expedition to study the Nambikwara and Tupi-Kawahib societies. At this time, his wife had an eye infection that prevented her from completing the study, which he concluded. This experience cemented Lévi-Strauss's professional identity as an anthropologist. In 1962, Lévi-Strauss published what is for many people his most important work, La Pensée Sauvage, translated into English as The Savage Mind.

The Savage Mind discusses not just "primitive" thought, a category defined by previous anthropologists, but also forms of thought common to all human beings. The first half of the book lays out Lévi-Strauss's theory of culture and mind, while the second half expands this account into a theory of history and social change. This latter part of the book engaged Lévi-Strauss in a heated debate with Jean-Paul Sartre over the nature of human freedom. On the one hand, Sartre's existentialist philosophy committed him to a position that human beings fundamentally were free to act as they pleased. On the other hand, Sartre also was a leftist who was committed to ideas such as that individuals were constrained by the ideologies imposed on them by the powerful. Lévi-Strauss presented his structuralist notion of agency in opposition to Sartre. Echoes of this debate between structuralism and existentialism eventually inspired the work of younger authors such as Pierre Bourdieu.

A worldwide celebrity, Lévi-Strauss spent the second half of the 1960s working on his master project, a four-volume study called Mythologiques. In it, he followed a single myth from the tip of South America and all of its variations from group to group north through Central America and eventually into the Arctic Circle, thus tracing the myth's cultural evolution from one end of the Western Hemisphere to the other. He accomplished this in a typically structuralist way, examining the underlying structure of relationships among the elements of the story rather than focusing on the content of the story itself. While Pensée Sauvage was a statement of Lévi-Strauss's big-picture theory, Mythologiques was an extended, four-volume example of analysis. Richly detailed and extremely long, it is less widely read than the much shorter and more accessible Pensée Sauvage, despite its position as Lévi-Strauss's masterwork.

Lévi-Strauss is one of the greatest ethnologists of all time with an ethnocentric vision of history and humanity. At a time when we are trying to give meaning to globalization, to build a fairer and more humane world. There is today a frightful disappearance of living species, be they plants or animals. And it's clear that the density of human beings has become so great, that they have begun to poison themselves. Lévi-Strauss is one of the dominating post-war influences and the leading exponent of Structuralism in the social sciences.