How Sutanuti village grew into a metropolis

A modest birth "24 August, 1690. This day as Sankraal, 1 ordered Captain Brooke to come up with a vessel to Chuttanuty (Sutanuti), where we arrived about noon, but found the place in deplor-able condition, nothing being left for our present accommodation, the rains falling day and night."

That's how Job Chamock, Governor of the Bay of Bengal, dropped anchor off the place that was to become Calcutta. Sutanuti, the village where Chamock landed, was one of a cluster of three villages — the other two were Govindapur and Kalikata, predecessors of most of today's southern and western Calcutta. It was the twilight hour of the Mughal empire, Aurangzeb having committed most of his resources and attention to a futile war in the Deccan. Back in England, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 had already put the country firmly in the grip of the nobility, property owners and wealthy merchants. Chamock, too, was the product of an age of change: he left Cromwell's England to arrive in India in 1655. By 1657 he had become a junior member of the Council of the Bay of Bengal at a salary of 20 pounds a year. In 1686 he became the Governor of the Council and had sailed upstream of Sutanuti, to be driven back by the army of the Muslim rulers of Bengal. In 1687, a dejected Charnock had even sailed out of Bengal to Madras in the frigate 'Defence'.

But the tide was turning in favour of the British as far as their relationship with the Mughal court was concerned. Though Aurangzeb never liked the Englishmen, he needed the help of their navy in safeguarding the yearly pilgrim traffic to Mecca. So he ordered his ministers to negotiate peace with Sir Joshua Child, chief of the Company's settlements in Bombay. A treaty was signed, and Charnock, armed this time round with a firman from the Emperor, reached Sutanuti on a day when "the rains were falling day and night".

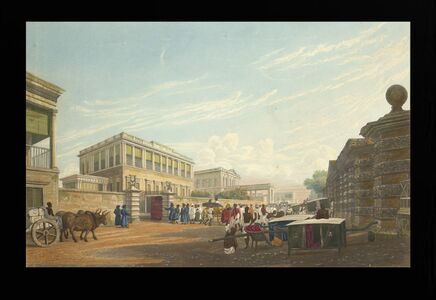

Dressed in a loose shirt and pyjamas, smoking a hookah and sipping arrack punch. Charnock transacted business — trading mostly in silk and saltpetre—from under a shady banyan tree. Upjohn's 1794 map locates the tree at today's Sealdah area, near the modern flyover and a good two miles from the Hooghly river, the only highway of colonial trade in seventeenth century Bengal. Charnock had chosen the eastern bank of the river against accepted practice: the French had chosen Chandernagore, on the western bank, as their colony in 1673; the Dutch had settled at Chinsurah and the Danes at Serampore — both on the west of the river. Besides, on the east of Charnock's new home lay a vast marshy swamp — which was later to become the fashionable Salt Lake—where the large surplus fish stock emitted a killer stench every winter. It was a vast bog, even the gradient was away from the river, leaving no room for natural drainage.

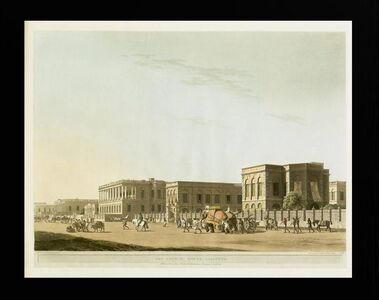

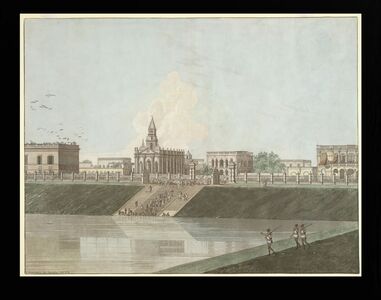

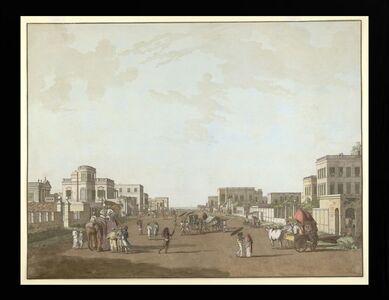

Between Sutanuti and Kalikata, the seat of the famed Kali temple, lay Chowringhee — now the heart of Calcutta, but a dense patch of forest in Charnock's time. The Seths and Basaks—the old textile merchants of Sutanuti—had their village close to Charnock's banyan tree, around the present north Calcutta. The Fort William, named after King William of Orange, was built in 16% out of brick-dust, molasses, lime and cut hemp. Garrisoned by 200 soldiers, it extended from the middle of Clive Street to the northern edge of Dalhousie Square. By then, however, Charnock had died. In 1698, the three villages were consolidated, and the Nawab of Bengal sold the entire block to the Company for Rs 1,300.

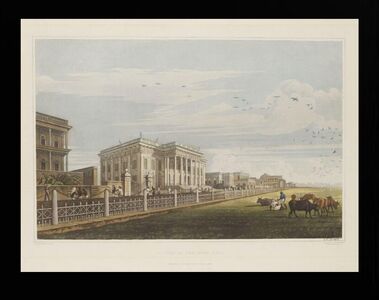

A urangzeb died in 1707. By then, the three villages, a thousand miles away from the seat of the dying empire, had acquired the name of Calcutta and weregradually becoming a beehive of activity. While the 'black' town grew northwards, along Chitpur Road, the European quarters of the city were fast taking shape. St Anne's Church came up in 1709; the Fort was completed in 1712; the expatriates opened their first theatre at Lalbazar in 1745. Soon afterwards, merchant John Surman led a deputation to Delhi to buy up another 38 villages, including Howrah.

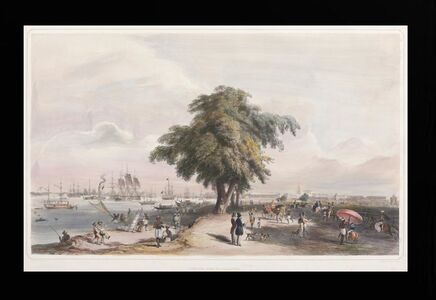

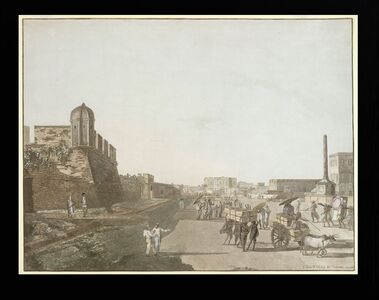

By 1742, when the Company had excavated the defensive Marhatta Ditch against the marauding hordes from the west, the European town had already expanded over an area of one square mile. The natives lived in an already congested sprawl, four miles in circumference and bound by the Hooghly on the west. The city thenrecorded a mixed population of four lakh. With 50 boats sailing into the river every year, the volume of trade in Calcutta had also touched a million pounds annually. However modest, the first 50 years in the life of Calcutta was only the overture to the imperial theme. At its end, the Whig gentlemen at the Company's headquarters on Leadenhall Street looked at an expanding empire with — in historian Philip Woodruff's words — "the incredulous elation...of a village grocer who has inherited a chain of department stores".

The year of the bhadralok

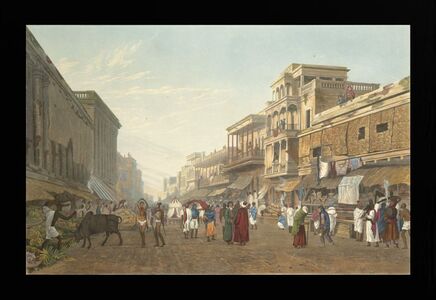

The native areas of Calcutta in the II early 19th century, inhabited mostly by Bengalis, were in stark contrast to the gorgeous mansions sprouting all over the European part of the city. The reputation of Calcutta in the rest of the world depended almost entirely on the mercantile activity centring around the white-inhabited hub of the city. But Cornwallis brought about 'Permanent Settlement' in 1793, which, among other things, created 'absentee landlords'. It is this idle class, rather than the incipient Bengali traders and entrepreneurs, which spawned the bhadralok of Bengal. They were the prime mov-ers in all major social changes in India in the 19th century, dominating the nation's cultural and political scene for a hundred years, first as an accomplice of the British and later as their critic.

Though the British rulers lived and ruled from behind an ethnic barrier, they consciously allowed changes in the staid colonial society when, by the 1813 Charter Act, a grant was earmarked for "introduction and promotion of a knowledge of the sciences among inhabitants of the British Territories in India". By 1817, the historic Hindu College had been founded; some of its early students were downright exhibitionists who, in their zeal to show off western education, often attracted collective disapproval of the society. But many of them turned out to be much more than the community's 'lunatic' fringe. Michael Madhusudan Dutt, the poet, created a new, elegant vocabulary for the Bengali language. Peary Chand Mitra and Ramtanu Lahiri were among the first Indian social chroniclers; besides, Mitra gave shape to the colloquial Bengali prose.

However, by the 1830s, the Company's government under Lord Bentinck, a Viceroy with radical leanings, had decided to throw open the floodgates of Western education, a policy which was not in practice in any British colony till then. In 1834, Thomas Babington Macaulay, the greatest 'Westernises' in the history of education in India, had arrived in Calcutta as the new Law Member. In 1835, the administration adopted a resolution which said: "The great objects of the British government ought to be the promotion of European literature and science." The Calcutta Medical College, the first institution of its kind in India, was established in 1835, and the first engineering college in 1856. Bethune College for Girls, again the first centre of Western education for women in India, came up in 1849. Calcutta University, the first among the universities in the country, was set up in 1857 — the year of the Mutiny.

Western education did not necessarily spark off a revolution of ideas. In fact, it created an avalanche of Bengali 'quilldrivers' or clerks—baboos, as the British derisively called them — earning their livelihood as copiers in managing agency houses, estate offices and the state administration.

The pen-pushers, however, never held the centrestage in old Calcutta. The limelight was stolen by a galaxy of Bengalis with a modern outlook: a reformer and spiritual leader like Rammohun Roy; a scholar and social activist like Iswarchandra Vidyasagar; novelist like Bankim Chandra Chatterjee; a religious radical like Keshub Chandra Sen; an intelligent revivalist like Swami Vivekananda; or a mystic like Ramakrishna. The enlightened Bengalis were then regarded by the British as friends of the regime, as different from the wily Marathas or refractory Afghans. So the bhadraloks had excellent rapport with the foreign masters, which they often put to good use. Roy's persuasion brought about the abolition of the suttee. Vidyasagar advocated for a legislation to allow widows to remarry.

But the Tagores are one family which towers above the other bhadraloks of Calcutta. The family patriarch, Dwarkanath, was hardly an idle beneficiary of the 'permanent settlement'. His Carr. Tagore and Company, the first Indian-owned joint stock company, was a commercial enterprise. He died young, but not before he had left the first Indian footmarks on some major avenues of modern business — insurance, banking, shipping. estate management, tea and coal.

Rabindranath Tagore. youngest son of Dwarkanath, was much more than just a literary figure. His writings — in prose and verse — his deep understanding of music, his paintings, as well as his unique lifestyle, gave Bengal a cultural identity. Even now, Tagore's books record the highest sale among all Indian authors, living or dead. There is hardly a town in India where either a public hall or a road is not named after him — a distinction which no other non-political Indian personality enjoys.

The influence of the bhadralok community in Indian life was waning ever since the capital of British India had shifted to Delhi in 1911 and Viceroy Curzon, for the first time in 1905, had raised the bogey of Bengal's partition.

Russian export of a jute substitute stopped after the Crimean War (1854-56). American farmers too began us-ing gunny bags for export and transhipment of grains. The first modern jute mill — Baranagar Jute Factory — was set up in 1872. By the end of the century, there were 14,000 power looms, employing over a lakh workers, mostly drawn from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. As the new century dawned, the Calcutta-centred jute mills had left Dundee far behind. The jute boom of the late nineteenth century thus heralded the golden years in the economic life of Calcutta. There was also a phenomenal spurt in tea exports, with Indian tea ousting Chinese tea from the British market by the 1890s. Besides, coal also contributed a major share or Calcutta's business earnings, not only feeding the railways which began op-erations in 1853, but eventually earn-ing export revenue too.

All these profitable channels of trade and industry were consolidated in the managing agency houses lining Clive Street: Bird & Co., Andrew Yule & Co, George Henderson & Co., Jardine Skinner, Gillanders Arbuthnot, Kettlewell Bullen, Ernshausen & Co., and F.W. Heilgers. Trade was so lucrative that Bengal Chamber of Commerce, founded in 1834, was sending generous aids to business buddies in England. In 1900, most of the Rs 53 crore disbursement in England, comprising 4.37 per cent of India's national income, was routed through Calcutta. As the cash registers jingled, the whole city throbbed in the second half of the last century with headlong commercial rush. The pontoon bridge between Howrah and Calcutta came up in 1872, the horse-drawn tram appeared in 1880 and a telephone system was installed in 1882. In the midst of the frenetic gold rush, the only one to bid farewell to Calcutta was Peninsula and Oriental (P&O) Steamship Company which shifted its headquarters from Garden Reach to Bombay, as the. Suez Canal had been completed by then, making Bombay so much closer to Liverpool than Calcutta. However, not even a small fraction of the city's affluence crossed the protected preserve of the whites to enter the narrow, streets of the black town, lined with rows upon rows of grimy houses, mostly mud and thatched. As late as 1914, nine lakh people in the native part of the city were living in just 45,000 houses. The literacy rate of Calcutta was a meagre nine per cent even at the turn of the century and 65 years after Bentinck had ushered in Western education. And the moral of the 'other' Calcutta was just as loose as its quality of life was low: in 1853, the year of the first locomotive in India, the city of four lakh people had 12,719 prostitutes. That would put every eighth woman in Calcutta on hire. Unlike Bombay, India's megapolis of the future, Calcutta's opulence was never shared by its original inhabitants. The Investor's India Year Book of 1914 shows that, in that year, Calcutta had 81.26 per cent of capital investment drawn from Europeans and a measly 2.87 per cent from Indians. On the other hand, Bombay had 48.63 per cent of its investment drawn from Indian sources. It was only in Calcutta that the British had a free run, unopposed by the locals. The affair went on until the Britishers' `marriage' with Bengal had gone stale, and they had shifted the capital to Delhi in 1911.