The Metro tunnel hitting an aquifer, a body of permeable rock which can contain or transmit groundwater, and the whole area of Bowbazar slowly crumbling, raises the ghost of a creek which has been lying dormant for centuries.

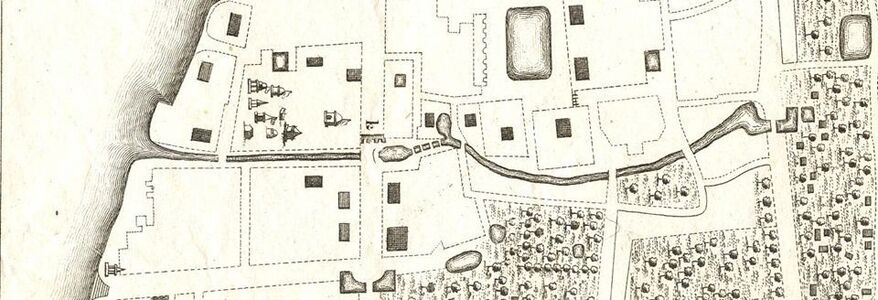

But this is not something that is unknown. I retrieved several maps of old Calcutta to check. The most significant maps are the one by Colonel Mark Wood in 1784-85 and the map of Calcutta and its Environs by A Upjohn in 1792-93. Going through these maps I found that a creek existed long back in the area where there is devastation.

The creek used to meander from the Hooghly at places between Chandpal Ghat and Babu Ghat, Hastings Street (Kiran Shankar Roy Road) and passed through Waterloo Street, Prinsep Street, Wellington Square, Creek Row, Sealdah and Beliaghata to Salt Lake in the east. It is this Creek that gave Creek Row its name, now Nilratan Sarkar Sarani.

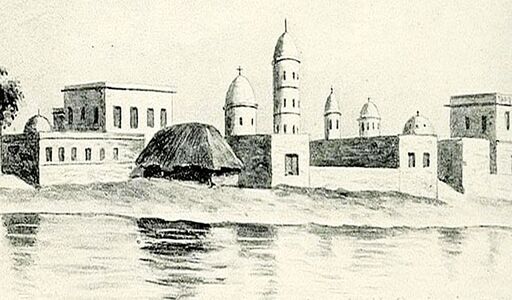

Significantly, the creek was a navigable channel till 1737 for even big barges, as mentioned by Cotton in his monumental work, Calcutta, Old and New; A Historical & Descriptive Handbook to the City. In the absence of proper roads, riverine routes were convenient for the British East India Company officials to venture out of Old Fort William, which was built where the GPO stands today. In fact, British officials excavated the creek for further navigability. According to Kolkata chronicler P T Nair, the name of the city originated from the word ‘Khal-Kata’, or creek excavation.

When the great tropical cyclone struck the city on October 11, 1737, it left an incredible trail of death and destruction. It destroyed the city’s first British church, St Anne, which was where the rotunda of the Writers’ Buildings is located. The storm winds, as reported in the East India Company documents, were felt 60 leagues (200 miles or 333km) inland and thousands of vessels were sunk. A big barge was blown nearly 4km into the creek, beyond the spot where Wellington Square, now known as Raja Subodh Mallik Square, today stands. Because of the wrecked barge, which was stuck there for quite a long time, the area used to be called Dingah Bhanga, loosely translated as broken barge. To identify the place where the barge was wrecked, the lane adjacent to the place was named Dingah Bhanga Lane. It was subsequently renamed Wellington Lane and now Raj Kumar Bose Lane.

It was the cyclone that sounded the creek’s death knell. The storm caused the creek to silt up. The stretch of Hastings Street was first filled up. But the Creek Row stretch remained a creek for a little longer, though the water flow stopped, since the gradient of the city is west-to east. “The old bed of the creek remained, long after the closing of its connection with the river had deprived it of its stream, and turned it into a ditch, which served to carry off the surface drainage. It was into this ditch, at what is now Wellington Square, that the sewers discharged their contents,” wrote Kathleen Blechynden in her ‘Calcutta Past and Present’ (1905).

Memories of the creek echo in local folklore and, especially names of places like Jelepara Lane, Jele is Bengali for fisherman, Sareng Lane, Sareng is the steward of a barge and Kaibartya Samaj, the society of fishermen. Jeleparar Sanga, fishermen’s group has remained alive for centuries. People in these areas recall that their forefathers used to catch fish and sell them at Janbazar and Fenwick Bazar. Their livelihood was dependent on the creek. But when the creek ceased to exist and they also changed their way of earning. For the last hundred years, none of them are engaged in fishing, but their customs remained those of fishermen, particularly many of their marriage ritual.

There are many Bot Tala literature which recounts residents in courtyards with flights of stairs where people could embark from a boat. Over the years, these have gone. But finding parts of boats during foundation work of buildings is not uncommon here. There are limericks and wood block prints on the subject.

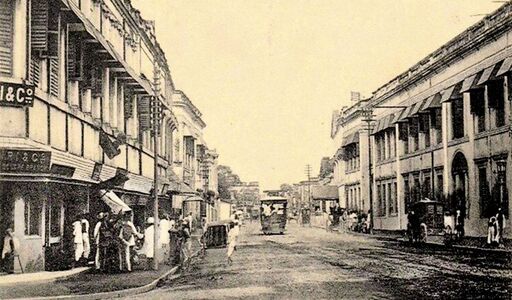

But Creek Row was not only an area where fisherman and boatman resided. It also became a hub of nationalist movement in the pre-Independence era. It had the office of Bande Mataram, the nationalist newspaper edited by Aurobindo Ghosh. But the heart of the nationalist movement was more nearby at 12, Wellington Square, the majestic mansion of Raja Subodh Mallik. Aurobindo lived in this house till his arrest. Leaders like Subhas Bose, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Mahatma Gandhi, and luminaries like Rabindranath and Nazrul used to come to visit this house.

In time, Creek Row also became a metaphor for academic and cultural excellence. Creek Row was the Harley Street of London, which has been noted since the 19th century for its large number of professionals, including specialists in medicine, surgery and other professionals. Right from eye surgeon Nihar Munshi to paediatrician Kshirode Chaudhury, the younger brother of Nirad C Chaudhury, they all used to live here. If you go back a little further, Dr Mahendra Lal Sarkar, the first Indian MD, lived nearby. Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar used to frequent Creek Row to discuss homoeopathy with Rajen Dutta, who is considered to be the father of Indian homoeopathy. Rajen Dutta was also the grandson of Akrur Dutta, a key merchant with the East India Company. Even Mother Teresa lived for a while at Creek Lane, off Creek Row, after she left Loreto House.

But everything bearing that history is being destroyed after the mammoth tunnel-boring machine hit the unmapped aquifer. Now the history of the creek and waterbodies of Bowbazar, where the subsidence happened, has suddenly assumed serious significance. The old maps of the city shows that all the houses are sitting right on top of the erstwhile creek.

I doubt whether Kolkata Metro Rail Corporation (KMRC), the executing agency of the East-West Metro, consulted the old maps to understand the situation below the surface. The accident has woken up the ghosts of a stream that once flowed through the heart of the city.

It is interesting to note that the history of the London Underground began in the 19th century with the construction of the Metropolitan Railway, the world's first underground railway. The Metropolitan Railway, which opened in 1863 using gas-lit wooden carriages hauled by steam locomotives, worked with the District Railway to complete London's Circle line in 1884. In 1905,the British Parliament requested The Advisory Board of Engineers co-opted with The Royal Commission of Traffic to look into the possibility of laying an underground railway network , in the second capital of the British Empire, Calcutta. Acting on this view , the Board embodies in the Report that : Calcutta is built on dangerous sloppy silt, with a very occasional thin bed of poor remains of carbonaceous clay and creeks running within the city, making it hazardous to build an underground railway. Quote from : The Condition, Improvement and Town Planning of the City of Calcutta and Contiguous Areas. The Richard Report. By E P Richard.

Kolkata’s biggest infrastructure undertaking in decades, the East-West Metro project estimated at Rs 8,575-crore has been thrown off track because a tunnel-boring machine hit an aquifer. That is why tunnelling 13 metres below the bed of the Hooghly was a cakewalk, compared with negotiating this site where the creek used to flow, allowing water ingress or permeability. When a body of water is filled up, the formation of underground water table can be highly fragmented and deceptive. The precarious geology of the Bowbazar area because of huge water flow points at the creek, which may be buried deep underneath the surface.

But what really tripped up this behemoth is the ghosts of the city’s past that few people remember now. The first clue lies in the name of a short road in an old part of the city: Creek Row. The stream that gave Creek Row and its extension Creek Lane its name may be long gone, but scratch below the surface, and it’s very much there. You can obliterate a canal or tank by filling it up, but you can hardly erase their underground imprints.

And with it now the over ground history. With the tunnel, a part of Calcutta will go buried. What a shame. If only we had consulted old maps to know what lay beneath.

- Read the original article in Bengali on this website.

- Read the original article on the Ananda Bazar Patrika website.